Vol. 1, No. 3

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - In this issue:

In this issue:

reviews of Wrath of the Spectre (TPB) and Day of Vengeance #4 / notes on allusions to Hamlet in Astonishing X-Men, the lost art of promo art, and remembering Jim Aparo / rants about the Purple Man and comic book metafiction

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

reviews

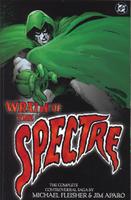

Wrath of the Spectre (TPB) (DC Comics)

Michael Fleisher (Writer) / Jim Aparo, Ernie Chua, Frank Thorne, Mike DeCarlo, and Pablo Marcos (Artists) / Jim Aparo, John Costanza, and Augustin Mas (Letterers) / Adrienne Roy (Colorist) The best comic I bought this week was DC’s collected edition of Michael Fleisher and Jim Aparo’s The Wrath of the Spectre, released earlier this year. David Fiore’s appreciation of Aparo’s work on these issues last week got me to pick it up, and I’m sure delighted that I did. What a read!

The best comic I bought this week was DC’s collected edition of Michael Fleisher and Jim Aparo’s The Wrath of the Spectre, released earlier this year. David Fiore’s appreciation of Aparo’s work on these issues last week got me to pick it up, and I’m sure delighted that I did. What a read!

Most of the stories follow a simple pattern of crime and retribution in which the Spectre metes out ghastly forms of poetic justice to evil men and the occasional evil woman. But don’t let the simplicity or (apparent) repetitiveness of the plots fool you. These stories are simultaneously deeply satisfying as well as deeply unsettling, and the peculiar form of elemental pleasure/horror they evoke springs from their amplification of a contradiction that is already inherent in the concept of the revenge ghost upon which the Spectre is based. Revenge ghosts are a staple of horror in every iteration of the genre, but the type of affect these ghosts generate is not adequately described by the term “horror.” As the cover to this issue of Beware from 1953 illustrates, the revenge ghost mixes horror with the idea of just deserts (in fact the latter ostensibly “justifies” the former, albeit not enough for Frederic Wertham). The result of this mixture is a bifurcated plot structure that complicates our reading experience by splitting our identification between the innocent victim/revenge ghost on the one hand (the justice plot) and the murderer/victim of the revenge ghost on the other (the horror plot). Thus, in a typical story of this type, we don’t care much about the original victim--they’re barely on stage before they’re dispatched, their sole function being to motivate (and embody) the action of supernatural revenge. The meat of the story is the haunting and grisly destruction of the murderer with whom we must sufficiently identify in order for the story to produce the desired effect of horror. Hence the contraction of the motivating murder (the murder of the innocent) and the expansion of the revenge murder (the murder of the guilty), a murder we “experience” more intensely through the story’s use of time and point of view (extensive scenes of flight and fear are usually given to the guilty victims, not the innocent ones). This double-plot ensures that our relation to the murderer is ambivalent: we are horrified by his torment at the hands of a genuinely frightening supernatural agency, and yet we also enjoy his inevitably horrific fate as form of justice, sadistically identifying with the revenge ghost itself, no matter how horrifying it appears. It is thus no contradiction for Uncle Creepy to entreat us: “Feast your bloodshot eyeballs on comics guaranteed to leave you senseless with delight!”

Revenge ghosts are a staple of horror in every iteration of the genre, but the type of affect these ghosts generate is not adequately described by the term “horror.” As the cover to this issue of Beware from 1953 illustrates, the revenge ghost mixes horror with the idea of just deserts (in fact the latter ostensibly “justifies” the former, albeit not enough for Frederic Wertham). The result of this mixture is a bifurcated plot structure that complicates our reading experience by splitting our identification between the innocent victim/revenge ghost on the one hand (the justice plot) and the murderer/victim of the revenge ghost on the other (the horror plot). Thus, in a typical story of this type, we don’t care much about the original victim--they’re barely on stage before they’re dispatched, their sole function being to motivate (and embody) the action of supernatural revenge. The meat of the story is the haunting and grisly destruction of the murderer with whom we must sufficiently identify in order for the story to produce the desired effect of horror. Hence the contraction of the motivating murder (the murder of the innocent) and the expansion of the revenge murder (the murder of the guilty), a murder we “experience” more intensely through the story’s use of time and point of view (extensive scenes of flight and fear are usually given to the guilty victims, not the innocent ones). This double-plot ensures that our relation to the murderer is ambivalent: we are horrified by his torment at the hands of a genuinely frightening supernatural agency, and yet we also enjoy his inevitably horrific fate as form of justice, sadistically identifying with the revenge ghost itself, no matter how horrifying it appears. It is thus no contradiction for Uncle Creepy to entreat us: “Feast your bloodshot eyeballs on comics guaranteed to leave you senseless with delight!” Fleishman and Aparo’s Spectre stories follow this double-structure, but with a very significant difference. In a typical EC story of this sort, one feels that, despite this structurally mandated ambivalence, the balance still ultimately tilts in the direction of horror. We might to some extent be invited to identify with the ghost, but it is very hard to reconcile the ghost’s manifestly “evil” appearance with the moral order it ostensibly embodies. In fact, the very monstrosity of the retribution (the thing that we find most horrifying) fatally undermines the story’s putative “moral” alibi. (Really, Mr. Wertham, these stories teach lessons!)

Fleishman and Aparo’s Spectre stories follow this double-structure, but with a very significant difference. In a typical EC story of this sort, one feels that, despite this structurally mandated ambivalence, the balance still ultimately tilts in the direction of horror. We might to some extent be invited to identify with the ghost, but it is very hard to reconcile the ghost’s manifestly “evil” appearance with the moral order it ostensibly embodies. In fact, the very monstrosity of the retribution (the thing that we find most horrifying) fatally undermines the story’s putative “moral” alibi. (Really, Mr. Wertham, these stories teach lessons!)

With the Spectre, however, the possibilities for identifying with the revenge ghost change substantially. Now the revenge ghost’s function is embodied in a single character who acts as sort of meta-phantom from which all revenge ghosts spring. (In other words, he embodies a structural feature of all revenge-ghost stories that normally remains implicit: the convention of the revenge ghost itself.)  This unique premise has many fascinating consequences, the most pertinent of which is that our increased ability to identify with the revenge ghost (now the story’s protagonist) thoroughly complicates the effect of these stories. The “horror” of 1950s horror comics is now supplemented by a much stronger “moral” component. But this does not mean that these stories are more reassuring. In fact, they are less so because what the expanded emphasis on the justice plot now makes visible is the possibility that horror resides within the actions of the “just” law itself.

This unique premise has many fascinating consequences, the most pertinent of which is that our increased ability to identify with the revenge ghost (now the story’s protagonist) thoroughly complicates the effect of these stories. The “horror” of 1950s horror comics is now supplemented by a much stronger “moral” component. But this does not mean that these stories are more reassuring. In fact, they are less so because what the expanded emphasis on the justice plot now makes visible is the possibility that horror resides within the actions of the “just” law itself. Despite the protests of certain stories in this collection which anxiously address this very question, the supernatural punishment of the criminal always feels excessive, no matter how evil a crime he has committed (and Fleisher pulls no punches here: these criminals are bad guys). Moreover, this excess is attributed not to a satanic-looking corpse whose ambiguous brand of “justice” is easy to dismiss, but to a superhero-ghost whose mission is implicitly divine. Thus, just as the Spectre’s embodiment of the revenge ghost’s function increases our identification with him, it also increases the extraordinary ambiguity of our response to his actions, and invites us to look critically at the notion of justice itself. This wonderfully subversive aspect of these stories (which has implications for a critique of capital punishment, among other things) is abetted by the fact that with the Spectre’s embodiment of the revenge ghost concept comes the possibility of self-consciousness, memory, learning, and change. We are no longer stuck in the endless cycle of repetition that was inevitable with stories featuring individual revenge ghosts who were all driven by the same abstract principle and who simply disappeared when their task was discharged.

Despite the protests of certain stories in this collection which anxiously address this very question, the supernatural punishment of the criminal always feels excessive, no matter how evil a crime he has committed (and Fleisher pulls no punches here: these criminals are bad guys). Moreover, this excess is attributed not to a satanic-looking corpse whose ambiguous brand of “justice” is easy to dismiss, but to a superhero-ghost whose mission is implicitly divine. Thus, just as the Spectre’s embodiment of the revenge ghost’s function increases our identification with him, it also increases the extraordinary ambiguity of our response to his actions, and invites us to look critically at the notion of justice itself. This wonderfully subversive aspect of these stories (which has implications for a critique of capital punishment, among other things) is abetted by the fact that with the Spectre’s embodiment of the revenge ghost concept comes the possibility of self-consciousness, memory, learning, and change. We are no longer stuck in the endless cycle of repetition that was inevitable with stories featuring individual revenge ghosts who were all driven by the same abstract principle and who simply disappeared when their task was discharged.  Later writers like Doug Moench and John Ostrander would go on to explore the ethical possibilities of the Spectre’s self-consciousness in considerable depth. But such an exploration is already developing in the Fleishman/Aparo stories where it takes the form of an external questioning of the Spectre’s methods via the character of Earl Crawford, a magazine freelancer who tracks the Spectre and articulates a more liberal point of view about the rights of the criminal.

Later writers like Doug Moench and John Ostrander would go on to explore the ethical possibilities of the Spectre’s self-consciousness in considerable depth. But such an exploration is already developing in the Fleishman/Aparo stories where it takes the form of an external questioning of the Spectre’s methods via the character of Earl Crawford, a magazine freelancer who tracks the Spectre and articulates a more liberal point of view about the rights of the criminal.  It is also implicit in the star-crossed relationship between would-be lovers Jim Corrigan and Gwendolyn Sterling, a relationship that ultimately leads Jim to ask “The Voice” to release him from his bondage to the vengeance-driven Spectre.

It is also implicit in the star-crossed relationship between would-be lovers Jim Corrigan and Gwendolyn Sterling, a relationship that ultimately leads Jim to ask “The Voice” to release him from his bondage to the vengeance-driven Spectre.

I am even tempted to see this critical exploration of justice reflected in a disturbingly topical tale entitled, “The Human Bombs and...the Spectre” in which a criminal scientist brainwashes people into becoming suicide bombers with a “stroboscopic hypno-wheel” of his own invention.  This “hypno-wheel” bears a suggestive visual similarity to later stories’ representation of “The Voice” as a set of bright lights that produce a similarly “hypnotic” effect on the helpless soul of Jim Corrigan to transform him in to the instrument of divine vengeance.

This “hypno-wheel” bears a suggestive visual similarity to later stories’ representation of “The Voice” as a set of bright lights that produce a similarly “hypnotic” effect on the helpless soul of Jim Corrigan to transform him in to the instrument of divine vengeance. Is the mad scientist’s hypno-wheel any different from the voice of god and the unyielding version of justice it sanctions in these tales? Are the Spectre’s divine acts of vengeance any less perverse than the mad scientist’s creation of human bombs? Beyond the genuinely visceral pleasures it unquestionably provides, the enduring strength of Fleisher and Aparo’s legendary work on the Spectre is that it does not allow us to answer any of these questions simply.

Is the mad scientist’s hypno-wheel any different from the voice of god and the unyielding version of justice it sanctions in these tales? Are the Spectre’s divine acts of vengeance any less perverse than the mad scientist’s creation of human bombs? Beyond the genuinely visceral pleasures it unquestionably provides, the enduring strength of Fleisher and Aparo’s legendary work on the Spectre is that it does not allow us to answer any of these questions simply.

Given the philosophical weightiness of Fleisher and Aparo’s Spectre, catching up with this character in the present day DCU is a journey from the sublime...

Day of Vengeance #4 (DC Comics)

Bill Willingham (Writer) / Justiano (Penciller) / Walden Wong (Inker) / Pat Brosseau (Letterer) / Chris Chuckay (Colorist)

...to the ridiculous. But not in a bad way.  Unleashing Bill Willingham on the magic pocket of the mainstream DCU was a very, very good idea. Day of Vengeance is flat-out fun. I’m enjoying all five Countdown minis probably more than is actually defensible, but this one has been the big surprise. I’ve always had an ambivalent relationship with magic-oriented books, but Willingham has sucked me in by focusing on character rather than plot (which is paper thin at best; someone on a message board described it as a giant slugfest, which is about right). The dust up between Captain Marvel and the Spectre (hardly recognizable as the same character that Fleisher and Aparo worked on) is deftly confined to the background, serving only as a pretense for generating amusing interactions among the loveable weirdos of DC’s magical Z-list.

Unleashing Bill Willingham on the magic pocket of the mainstream DCU was a very, very good idea. Day of Vengeance is flat-out fun. I’m enjoying all five Countdown minis probably more than is actually defensible, but this one has been the big surprise. I’ve always had an ambivalent relationship with magic-oriented books, but Willingham has sucked me in by focusing on character rather than plot (which is paper thin at best; someone on a message board described it as a giant slugfest, which is about right). The dust up between Captain Marvel and the Spectre (hardly recognizable as the same character that Fleisher and Aparo worked on) is deftly confined to the background, serving only as a pretense for generating amusing interactions among the loveable weirdos of DC’s magical Z-list.  Detective Chimp, Nightshade, Enchantress, Ragman, Shining Knight, Blue Devil: I feel like I know these people. (And in one particular case, I’m worried that I am one of these people). Besides, I’m a sucker for “assembling the super-team” stories (probably why I adored issues #1-6 of Bendis’s New Avengers), and here, the assembly of a team of supermagicians hybridizes the magical characters with superheroes in a way that makes them extra-palatable to an unreconstructed superhero geek like myself.

Detective Chimp, Nightshade, Enchantress, Ragman, Shining Knight, Blue Devil: I feel like I know these people. (And in one particular case, I’m worried that I am one of these people). Besides, I’m a sucker for “assembling the super-team” stories (probably why I adored issues #1-6 of Bendis’s New Avengers), and here, the assembly of a team of supermagicians hybridizes the magical characters with superheroes in a way that makes them extra-palatable to an unreconstructed superhero geek like myself. Granted, a few of the jokes are a bit broad. But I laughed out loud at least four times when reading this issue, and I laughed the second and third times I read it too. (Pathetically, I’m still giggling over the third-last page of issue two from two months ago.) For this, Justiano and Wong’s phenomenal, nutty artwork deserves as much credit as Willingham’s script. The scenes of Detective Chimp’s memories on page two, and the panel of Chimp and Nightshade’s awkward coffee klatch with Mr. Zechlin on page four are hilarious even without the dialogue. What’s more, the cartoony flare of the art perfectly bridges the potentially jarring gap between the essentially comic content of the story and the larger, more portentous, Crisis-story frame.

Granted, a few of the jokes are a bit broad. But I laughed out loud at least four times when reading this issue, and I laughed the second and third times I read it too. (Pathetically, I’m still giggling over the third-last page of issue two from two months ago.) For this, Justiano and Wong’s phenomenal, nutty artwork deserves as much credit as Willingham’s script. The scenes of Detective Chimp’s memories on page two, and the panel of Chimp and Nightshade’s awkward coffee klatch with Mr. Zechlin on page four are hilarious even without the dialogue. What’s more, the cartoony flare of the art perfectly bridges the potentially jarring gap between the essentially comic content of the story and the larger, more portentous, Crisis-story frame.

I do have one teensy gripe, and here I must echo Johanna Draper Carlson’s complaint about the characterization of Blue Devil; his personality (what I recall of it) seems to have been filched by Ragman. Perhaps all those years of bouncing drunken magicians hardened him. In any event, I look forward to learning all of the details when the Shadowpact ongoing by the same creative team premiers later this year. Um...right?

notes

Allusion Watch: Alas, Poor Yorick! Meaningful or not? The visual citation of one of the most famous and frequently reproduced and parodied scenes from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in this week’s Astonishing X-Men has me wondering...

Meaningful or not? The visual citation of one of the most famous and frequently reproduced and parodied scenes from Shakespeare’s Hamlet in this week’s Astonishing X-Men has me wondering... In Shakespeare’s play, the troubled, indecisive avenger, Prince Hamlet, treats us to a grimly ironic soliloquy on the inevitability of death when he is confronted with the skull of his beloved childhood Jester, Yorick:

In Shakespeare’s play, the troubled, indecisive avenger, Prince Hamlet, treats us to a grimly ironic soliloquy on the inevitability of death when he is confronted with the skull of his beloved childhood Jester, Yorick:

Alas, poor Yorick! I knew him, Horatio: a fellowHere in Astonishing, Professor X ruminates about his special relationship with Jean Grey when he confronts the head of his homicidal “daughter,” Danger, which he has just severed with an axe.

of infinite jest, of most excellent fancy: he hath

borne me on his back a thousand times; and now, how

abhorred in my imagination it is! my gorge rims at

it. Here hung those lips that I have kissed I know

not how oft. Where be your gibes now? your

gambols? your songs? your flashes of merriment,

that were wont to set the table on a roar? Not one

now, to mock your own grinning? quite chap-fallen?

Now get you to my lady's chamber, and tell her, let

her paint an inch thick, to this favour she must

come; make her laugh at that.

(Shakespeare, Hamlet, act V, scene i)

They seem pretty unrelated, but there’s more of a basis for comparison than one might think. Both versions of the scene are confrontations with dead (or almost “dead”) characters who are not exactly blood relatives, but are indeed very nearly relations, and are in both cases, extremely intimate ones: the childhood jester that Hamlet loved and the non-human “child” Xavier’s mind. Moreover, both scenes are on some level confrontations with death. And both have the key player making an allusion to a dead, absent woman. Hamlet refers to “my lady” (presumably his girlfriend Ophelia), pointing out that even if she applies makeup to make herself look younger, she’ll end up just as dead as poor Yorick (which turns out to be ironic since, unbeknownst to him, Ophelia is already dead--her funeral procession wanders through the graveyard a few lines later); similarly, Charles refers to Jean, who is also both absent and dead (or at least as dead as Jean gets).

Because the scene in Astonishing culminates in Charles’s casual chucking away of his “daughter’s” head (reinforcing his preference for his real “daughter” Jean), the allusion is parodic and its purpose appears to be simply to provide a convenient contrast between the mental fragility of famously indecisive Hamlet and the iron will of Prof. X, who, unlike Hamlet, is stoically unphased by his symbolic close encounter with death and guilt. (Hamlet, you will recall, ends up falling to bits and flinging himself about in Ophelia’s grave with fellow hysteric, Laertes.) Well done, Mr. Whedon!

Because the scene in Astonishing culminates in Charles’s casual chucking away of his “daughter’s” head (reinforcing his preference for his real “daughter” Jean), the allusion is parodic and its purpose appears to be simply to provide a convenient contrast between the mental fragility of famously indecisive Hamlet and the iron will of Prof. X, who, unlike Hamlet, is stoically unphased by his symbolic close encounter with death and guilt. (Hamlet, you will recall, ends up falling to bits and flinging himself about in Ophelia’s grave with fellow hysteric, Laertes.) Well done, Mr. Whedon! Moreover, we’ve seen this scene cited in the X-Men before--and in Genosha, no less. The second issue of Grant Morrison’s “E is for Extinction” arc had Beast quoting the Bard once again, at least implicitly, to comment on the nature of mortality in the context of genocide. Is Whedon quoting this scene too? Are there more pulse-pounding layers of allusion to peel back? Stay tuned!

Moreover, we’ve seen this scene cited in the X-Men before--and in Genosha, no less. The second issue of Grant Morrison’s “E is for Extinction” arc had Beast quoting the Bard once again, at least implicitly, to comment on the nature of mortality in the context of genocide. Is Whedon quoting this scene too? Are there more pulse-pounding layers of allusion to peel back? Stay tuned!The Lost Art of Promo Art

Remember when companies commissioned original art to promote their books? Tonyznet.com's Nostalgia Zone has the complete issue of DC Sampler #2 from 1984 in all its splendor (my own copy of this issue suffered what was probably a common fate: being disassembled and cut up to make posters for the bedroom walls...).

Among the fantastic promotional art it contained were two-page spreads for The New Teen Titans, Atari Force, Blue Devil, Legion of Superheroes, Swamp Thing, Vigilante, Warlord, Jemm Son of Saturn, Batman and the Outsiders, Infinity Inc., Justice League of America, Thriller, Star Trek, Amethyst, and DC Blue Ribbon Digests. Ah, memories.

Among the fantastic promotional art it contained were two-page spreads for The New Teen Titans, Atari Force, Blue Devil, Legion of Superheroes, Swamp Thing, Vigilante, Warlord, Jemm Son of Saturn, Batman and the Outsiders, Infinity Inc., Justice League of America, Thriller, Star Trek, Amethyst, and DC Blue Ribbon Digests. Ah, memories.Remembering Jim Aparo

In addition to the great set of links compiled by Tegan, here are a couple of other really nice posts from last week from Ramblings and Left of the Dial.

In addition to the great set of links compiled by Tegan, here are a couple of other really nice posts from last week from Ramblings and Left of the Dial.Um, er, gosh...

I had a number of really nice suprises this week. Ian Brill of Brill Building said some very kind things about the site--thanks Ian! You really made my day. Thanks also to David from Clandestine Critic, Conductor from Hatful of Hollow, and John from Sore Eyes for the links and props. I feel all, um, er, gosh... Thank you one and all!

rants

The Metafiction Police

I’m sorry, but I’m just not enjoying the Purple Man. His appearance in New Avengers was fine, but his role in New Thunderbolts is hobbling the relaunch of this once-great title.

I’m sorry, but I’m just not enjoying the Purple Man. His appearance in New Avengers was fine, but his role in New Thunderbolts is hobbling the relaunch of this once-great title. Last week, I groused about the Paul Jenkins cameo in New Avengers; in that instance, I was irked by the sudden shattering of the horizon of expectation that the series had established up until that point. Successful metafiction, in my view, tends to be systemic. That is, metafiction works for me when self-consciousness is built into the structure of the story as a founding presupposition, rather than providing a jarring “surprise!” cliffhanger. Systemic metafiction is very difficult to achieve in mainstream superhero books because the horizon of expectations for most superhero fantasy on books that have gone on for 400+ issues is incredibly entrenched, and the genre itself is generally hostile to metafiction, its entire point being to free us from self-consciousness.

There are exceptions, of course. But they tend to follow a pattern. Grant Morrison on Animal Man, David Mack on Daredevil, John Byrne on She-Hulk: all these examples of successful superhero metafiction are the work of comic book “auteurs” whose tenure on a series announces a recognizable break in the usual horizon of expectations and whose very name often indicates a raising of the “literary” or philosophical stakes. (Case in point: DC’s ad campaign for Seven Soldiers actually features a photograph of Morrison and announces that the series is “From the mind of...” Morrison’s genius has become a brand--an irony that would not be lost on Morrison himself.) Moreover, what all three of these examples of comic book metafiction have in common is an interest in either the nature of the comic book medium and its conventions as such, the relationship between representation and reality, or both. They are, in other words, primarily concerned with exploring metafictional questions using the superhero as a point of entry; the breaking of the fourth wall in their work is not incidental, it isn’t just a neat twist or an cheap in-joke, and it certainly isn’t introduced as a way of solving continuity problems in the context of a superhero universe. The only reason that Morrison, Mack, and Byrne are able to get away with exploring metafictional questions within a regular superhero universe is that their metafictional stories do not seem to actually take place within that universe because the stories themselves violate the conventions of that regular fantasy universe so drastically. The problem with the Paul Jenkins appearance in New Avengers #7 is that it seems to want to have it both ways--to sustain the conventional universe in the presence of metafiction--and the result, for me at least, is an irreconcilable narrative split.

There are exceptions, of course. But they tend to follow a pattern. Grant Morrison on Animal Man, David Mack on Daredevil, John Byrne on She-Hulk: all these examples of successful superhero metafiction are the work of comic book “auteurs” whose tenure on a series announces a recognizable break in the usual horizon of expectations and whose very name often indicates a raising of the “literary” or philosophical stakes. (Case in point: DC’s ad campaign for Seven Soldiers actually features a photograph of Morrison and announces that the series is “From the mind of...” Morrison’s genius has become a brand--an irony that would not be lost on Morrison himself.) Moreover, what all three of these examples of comic book metafiction have in common is an interest in either the nature of the comic book medium and its conventions as such, the relationship between representation and reality, or both. They are, in other words, primarily concerned with exploring metafictional questions using the superhero as a point of entry; the breaking of the fourth wall in their work is not incidental, it isn’t just a neat twist or an cheap in-joke, and it certainly isn’t introduced as a way of solving continuity problems in the context of a superhero universe. The only reason that Morrison, Mack, and Byrne are able to get away with exploring metafictional questions within a regular superhero universe is that their metafictional stories do not seem to actually take place within that universe because the stories themselves violate the conventions of that regular fantasy universe so drastically. The problem with the Paul Jenkins appearance in New Avengers #7 is that it seems to want to have it both ways--to sustain the conventional universe in the presence of metafiction--and the result, for me at least, is an irreconcilable narrative split.  My problem with the Purple Man in New Thunderbolts is basically the same as this, even though it takes a different form. Here we don’t have the unwelcome parachuting of a real comic book writer into the pages of our new favorite action/adventure book, we have his fictional proxy: the seemingly omnipotent supervillain who styles himself as a “writer.” Like all writers he wants to write a good story and good stories require conflict. Fortunately, his powers allow him to manipulate his “characters” in any way that suits the generation of his “plot.” Etc. The metaphor is too obvious, and that’s the problem. We are made all too painfully aware of the parallels between the machinations of the Purple Man and those of real series writer Fabian Nicieza, since both appear to have identical aims: torturing the characters, producing unfathomably Byzantine conspiracies, generating twists and surprises to keep things interesting. The result is a reading experience that is almost impossible to get into because disbelief is never adequately suspended.

My problem with the Purple Man in New Thunderbolts is basically the same as this, even though it takes a different form. Here we don’t have the unwelcome parachuting of a real comic book writer into the pages of our new favorite action/adventure book, we have his fictional proxy: the seemingly omnipotent supervillain who styles himself as a “writer.” Like all writers he wants to write a good story and good stories require conflict. Fortunately, his powers allow him to manipulate his “characters” in any way that suits the generation of his “plot.” Etc. The metaphor is too obvious, and that’s the problem. We are made all too painfully aware of the parallels between the machinations of the Purple Man and those of real series writer Fabian Nicieza, since both appear to have identical aims: torturing the characters, producing unfathomably Byzantine conspiracies, generating twists and surprises to keep things interesting. The result is a reading experience that is almost impossible to get into because disbelief is never adequately suspended. Don’t get me wrong. I’m all in favor of torturing the characters and entangling them within an absurdly vast and indecipherable conspiracy. That’s why I’m reading Thunderbolts and why I was so pleased that Marvel decided to give the series another shot. In its heyday, the first run was one of the best guilty pleasures on the stands. But thematizing the premise of the series (jaw-dropping twists! unbelievable betrayals! mystery characters!) and embodying the process of the story’s composition drains all the life out of it. If the point of the twists and turns is simply to satisfy the whims of a sadistic villain, we’re denied the fun of trying to fathom the meaning of the twists. Sadism is boring, and even if there is some deeper conspiracy at play here beyond the Purple Man’s puerile rape fantasies (and I hope there is!), so far, I don’t even care enough to speculate about what it might be. I’m skimming along the surface of a book that was once a treat to dive into. I thought that Fabian did a fantastic job of following up Kurt Busiek’s defining run on the series the first time around. In fact, Fabian got me hooked: I only jumped on board the series after he had taken over, and then went back and read the series from the beginning. Here’s hoping that the best is yet come.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m all in favor of torturing the characters and entangling them within an absurdly vast and indecipherable conspiracy. That’s why I’m reading Thunderbolts and why I was so pleased that Marvel decided to give the series another shot. In its heyday, the first run was one of the best guilty pleasures on the stands. But thematizing the premise of the series (jaw-dropping twists! unbelievable betrayals! mystery characters!) and embodying the process of the story’s composition drains all the life out of it. If the point of the twists and turns is simply to satisfy the whims of a sadistic villain, we’re denied the fun of trying to fathom the meaning of the twists. Sadism is boring, and even if there is some deeper conspiracy at play here beyond the Purple Man’s puerile rape fantasies (and I hope there is!), so far, I don’t even care enough to speculate about what it might be. I’m skimming along the surface of a book that was once a treat to dive into. I thought that Fabian did a fantastic job of following up Kurt Busiek’s defining run on the series the first time around. In fact, Fabian got me hooked: I only jumped on board the series after he had taken over, and then went back and read the series from the beginning. Here’s hoping that the best is yet come.This is all to say that I prefer my comic book metafiction in one pile and my superhero fantasy in another. (I say this in the interests of the full critical disclosure that Harvey Jerkwater sagely called for over at Filing Cabinet of the Damned last week!) And yet, there are still some exceptions, beyond those of Morrison, Mack, and Byrne accounted for above. Next week, if all goes according to plan, I will try to account for one of these--the “incredible” Fantastic Four #176. In the meantime, if you care to pass on any other examples of good comic book metafiction, I’d love to hear them. (If anyone can suggest a better, more accurate term than “comic book metafiction,” I’d be grateful to hear that too!)

No comments:

Post a Comment