This is arguably the best and certainly the most genuinely moving issue of John Byrne’s legendary run on the Fantastic Four in the mid-eighties.  The story is simple and devastating. Sue has been hospitalized because of complications with her second pregnancy--complications brought on by the team’s exposure to radiation during an adventure in the Negative Zone. On the advice of several notable super-powered scientists (Dr. Michael Morbius, Dr. Walter Langkowski, and Dr. Bruce Banner), Reed seeks out radiation expert Dr. Otto Octavius (the villainous Doctor Octopus) in the hopes that he can help cure Sue and save their unborn child. The problem, of course, it that Octavius is a dangerous psychotic. The altruistic side of his personality has long been suppressed by the madness that overtook him following the radiation accident that psionically fused his robotic “octopus” arms to his brain. Reed visits Octavius in the psychiatric institution where he has been locked up, and after apparently curing him and securing his release, attempts to bring him to the hospital to examine Sue.

The story is simple and devastating. Sue has been hospitalized because of complications with her second pregnancy--complications brought on by the team’s exposure to radiation during an adventure in the Negative Zone. On the advice of several notable super-powered scientists (Dr. Michael Morbius, Dr. Walter Langkowski, and Dr. Bruce Banner), Reed seeks out radiation expert Dr. Otto Octavius (the villainous Doctor Octopus) in the hopes that he can help cure Sue and save their unborn child. The problem, of course, it that Octavius is a dangerous psychotic. The altruistic side of his personality has long been suppressed by the madness that overtook him following the radiation accident that psionically fused his robotic “octopus” arms to his brain. Reed visits Octavius in the psychiatric institution where he has been locked up, and after apparently curing him and securing his release, attempts to bring him to the hospital to examine Sue.

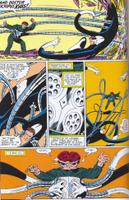

En route, however, Octavius suffers a relapse and is reunited with his robotic arms, which seem to be following the dictates of Octavius’s deranged unconscious, breaking out of a maximum security vault across town when a billboard reminds him of his pathological hatred for Spiderman. What follows is a spectacular battle over the rooftops of Manhattan in which the elastic, amorphous body of Mr. Fantastic and the thrashing, serpentine arms of Doctor Octopus coil and intertwine in a deadly struggle for mastery. Ultimately, Reed shuts down his opponent’s metal tentacles and succeeds in convincing him to help Susan by admitting the superiority of Octopus’s knowledge in the area of radiation. The pair arrive at the hospital, but it is too late. The presiding physician informs Reed that Sue is alright, but the baby died just over thirty minutes ago. What makes this issue so powerful is that Byrne tells the story from Reed’s point of view, not Susan’s, using the brilliantly conceived battle between Reed and Octavius as a discrete but potent visual metaphor for suggesting what the story itself does not show: the tragically understated “small loss” that gives the story its title. It would have been both inappropriate and emotionally less effective, I think, to actually represent Sue’s miscarriage directly. The loss of a child is too personal and too unnamable a grief to bear direct representation—any attempt at which risks trivializing or distorting the experience. It is a loss that is best conveyed indirectly, through absence, silence, and suggestion. The sickeningly effective understatement of the title; the awful chaos of Doctor Octopus’s arms which smash everything in their path, writhing and convulsing uncontrollably; the thick black border of the final panel that bears down on Reed as he is told, threatening to swallow him up, to swallow up everything, including representation itself. These are the signs of that unrepresentable event. That loss. That abjection.

What makes this issue so powerful is that Byrne tells the story from Reed’s point of view, not Susan’s, using the brilliantly conceived battle between Reed and Octavius as a discrete but potent visual metaphor for suggesting what the story itself does not show: the tragically understated “small loss” that gives the story its title. It would have been both inappropriate and emotionally less effective, I think, to actually represent Sue’s miscarriage directly. The loss of a child is too personal and too unnamable a grief to bear direct representation—any attempt at which risks trivializing or distorting the experience. It is a loss that is best conveyed indirectly, through absence, silence, and suggestion. The sickeningly effective understatement of the title; the awful chaos of Doctor Octopus’s arms which smash everything in their path, writhing and convulsing uncontrollably; the thick black border of the final panel that bears down on Reed as he is told, threatening to swallow him up, to swallow up everything, including representation itself. These are the signs of that unrepresentable event. That loss. That abjection. This comic repays rereading. For knowledge of the ending transforms our understanding of that awful, gut-wrenching battle over Manhattan. As Reed and Octopus fight, Sue is losing her baby. And as Reed struggles to subdue the rampaging arms (which are significantly separated from Octavius’s body at the beginning of the fight), it is now possible to see that what he is struggling to subdue is another chaotic, uncontrollable event that is taking place at that very moment in a small room in a hospital across town. Reed’s successful deactivation of Octavius’s robot arms by plugging up all the holes in his foe’s chest plate with his elasticized fingers retrospectively takes on the quality of a wish-fulfillment--a fantasy of an agency that Reed ultimately lacks in the real story that is going on somewhere else.

This comic repays rereading. For knowledge of the ending transforms our understanding of that awful, gut-wrenching battle over Manhattan. As Reed and Octopus fight, Sue is losing her baby. And as Reed struggles to subdue the rampaging arms (which are significantly separated from Octavius’s body at the beginning of the fight), it is now possible to see that what he is struggling to subdue is another chaotic, uncontrollable event that is taking place at that very moment in a small room in a hospital across town. Reed’s successful deactivation of Octavius’s robot arms by plugging up all the holes in his foe’s chest plate with his elasticized fingers retrospectively takes on the quality of a wish-fulfillment--a fantasy of an agency that Reed ultimately lacks in the real story that is going on somewhere else.

But the battle between Reed and Octopus is not simply a metaphor for Sue’s miscarriage or for Reed’s struggle to prevent it. It is also a metaphor for the sense of guilt Reed feels for having failed to achieve this end, and for being absent at the very moment that Susan needed him the most. That such guilt is “irrational” and unwarranted makes little difference to him who is tortured by it. The crucial clue comes when Reed, wrapped in and around the coils of the metal arms, observes, “I’ve never had to deal with an unliving analogue to my powers”--in other words, he is waging a symbolic struggle less against an external foe than against a double or “analogue” of himself. The deadly metal tentacles that pound, stretch, and pinion Reed’s formless body is as good a visual representation of an individual’s struggle with such inner torment as has ever been put down on paper.  Byrne has become a polarizing figure in recent years, but whatever one thinks of the man and his work, “A Small Loss” is a genuine and lasting aesthetic achievement. It shows unequivocally the symbolic potential of the conventional superhero medium to represent fundamental human experiences in dignified and deeply moving ways. More specifically, it shows how superhero tropes like elastic bodies and metal arms can be “stretched” into potent metaphors for the heroic power of the ordinary individual when faced with the all too human tragedies of loss, grief, and guilt. Ultimately, what Byrne has given us is a story about the fundamental powerlessness that haunts every human being: the brute unyielding fact of the body and its limits. It’s an important story, and one we are fortunate to have.

Byrne has become a polarizing figure in recent years, but whatever one thinks of the man and his work, “A Small Loss” is a genuine and lasting aesthetic achievement. It shows unequivocally the symbolic potential of the conventional superhero medium to represent fundamental human experiences in dignified and deeply moving ways. More specifically, it shows how superhero tropes like elastic bodies and metal arms can be “stretched” into potent metaphors for the heroic power of the ordinary individual when faced with the all too human tragedies of loss, grief, and guilt. Ultimately, what Byrne has given us is a story about the fundamental powerlessness that haunts every human being: the brute unyielding fact of the body and its limits. It’s an important story, and one we are fortunate to have.

Saturday, July 09, 2005

“The World’s Greatest Comic Magazine” (Part 3): The Guilt of “A Small Loss” in Fantastic Four #267

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment