I: Clichés

I: Clichés

I was eight years old in 1980, when I saw Al Milgrom’s powerful cover for The Amazing Spider-Man #205 staring back at me from the comics rack. Love at first sight: the cliché fits in more ways than one. What was it about that cover?

Spidey is in the foreground, looking up. And I am right there behind him, looking over his shoulder at the incredible thing he sees: a masked woman all in black, long white hair whipping behind her, has wrenched loose the chain of a crystal chandelier and is pulled behind it as it comes crashing down. Headed straight for Spidey. And for me.

Spider-Man is the ultimate point-of-view character for a boy of eight, and Milgrom makes this relationship explicit with the angle of this phenomenal image. But what is it that me and Spidey see exactly? What is this glittering crystal object? This unlikely weapon trailed by a woman with hair as silver-white as the diamond-shaped pendants that swing dangerously from its frame like knives?

Back then, I couldn’t have articulated what this cover showed me. I knew only that it was different from other comic covers I’d seen, that it evoked a strange, powerful feeling, and that I wanted it very badly. This strange, powerful feeling was, of course, desire. And what this cover showed me, I think, was a story about love.

This, at least, is what it shows me now, and the love story it tells is a very particular one about a certain way of characterizing romantic love that is as old as Cupid and his merciless bow. This version of the story is so old, in fact, that it has become one of the most potent clichés through which we try to talk about this surprising, joyful, bewildering experience that we struggle to name with the help of Hallmark or with the florid gasps of our own bad poetry.

Despite its costumes and overtly agonistic context, in other words, the story this cover tells is neither fatal nor violent, except to the degree that love--and especially the cliché of love at first sight--can be said to partake of these qualities: the piercing stare, the arrow to the heart. What it tells above all is a story about what romantic love looks like to an eight-year-old boy, and sometimes--though not always--what it looks like to that boy who is now, inexplicably, an adult.

So what does it look like? Frightening and beautiful all at once. Excessive. Cataclysmic. Blissful. Something you don’t defend yourself against. It looks like a thrashing anemone made out of glass. Like crystal jewels that make a pure bright sound as they fall. Like a chaos of light and sharp edges. Like something precious that wounds.

And behind it, propelling it, yet being pulled down by it too, is a woman you do not know. She is its agent and at the same time its victim. A woman in black who brings “bad luck”--or seems to. (Love is always “bad luck” for the ego, which it shatters, if we’re lucky.)

What does love look like? On the cover of The Amazing Spider-Man #205, it looks like a falling chandelier, with you caught beneath it. Unable to move or look away. Like Spidey, you are dazzled by this surprise. You hold your breath and just stand there, transfixed, as if waiting to be pierced by a shard, or by an arrow…

What I remember: It’s evening and I’ve gone to the mall with my mom after a swimming lesson for a treat. I’m crouched in front of a magazine rack, scanning the colored covers. I choose this comic because I think the chandelier is beautiful.

II: Obsessions The Amazing Spider-Man #205 is an unlikely starting-point for a discourse on love. Far from telling us anything meaningful, its story seems to epitomize exactly the sort of reactionary and defensive narrative about love that we might expect to find in a genre that markets itself as Boy’s Own fantasy, an exclusive genre that practically posts a sign on the treehouse: NO GIRLS ALLOWED. In such a genre, we would expect love to “feminized.” To be pathologized as a female “problem,” and also to be treated as an emasculating threat to the male hero. We would expect it to be personified in the character of the ubiquitous femme fatale--the genre’s most essential, even foundational villain. We would expect her to embody all the most sexist, even misogynist clichés of the succubus: she would be feral, dangerous, single-minded, psychotic. A black hole of desire for whom “love” involves none of the mutuality that we recognize in adult relationships, but is merely an other name for possession, mastery, and appetite.

The Amazing Spider-Man #205 is an unlikely starting-point for a discourse on love. Far from telling us anything meaningful, its story seems to epitomize exactly the sort of reactionary and defensive narrative about love that we might expect to find in a genre that markets itself as Boy’s Own fantasy, an exclusive genre that practically posts a sign on the treehouse: NO GIRLS ALLOWED. In such a genre, we would expect love to “feminized.” To be pathologized as a female “problem,” and also to be treated as an emasculating threat to the male hero. We would expect it to be personified in the character of the ubiquitous femme fatale--the genre’s most essential, even foundational villain. We would expect her to embody all the most sexist, even misogynist clichés of the succubus: she would be feral, dangerous, single-minded, psychotic. A black hole of desire for whom “love” involves none of the mutuality that we recognize in adult relationships, but is merely an other name for possession, mastery, and appetite.

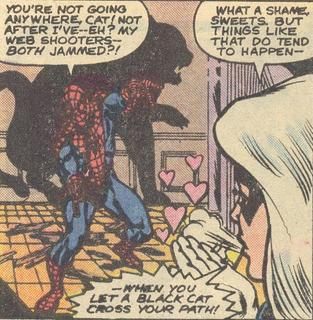

Superficially, at least, David Michelinie seems to give us a barely modified version of such a scenario in this story about the Black Cat’s obsession with Spider-Man--a story whose very title, “...In Love and War,” conjures some of the clichés I’ve just described.  The story, in brief, is that costumed cat-burglar Felicia Hardy is at large in Manhattan, stealing famous artifacts associated with love and romance. After a series of romantically-charged skirmishes with the Black Cat in museums and penthouses, Spidey concludes that her burglaries are symptoms of an obsession with her recently deceased cat-burglar father. In the final pages of the issue, however, Spidey learns the true “secret” of the Black Cat that was advertised on the cover: her obsession has not been with her father per se, but with Spider-Man himself. Spidey diagnoses her Electra Complex in a discreet inner-monologue that is a tour-de-force of Mighty Marvel psychobabble:

The story, in brief, is that costumed cat-burglar Felicia Hardy is at large in Manhattan, stealing famous artifacts associated with love and romance. After a series of romantically-charged skirmishes with the Black Cat in museums and penthouses, Spidey concludes that her burglaries are symptoms of an obsession with her recently deceased cat-burglar father. In the final pages of the issue, however, Spidey learns the true “secret” of the Black Cat that was advertised on the cover: her obsession has not been with her father per se, but with Spider-Man himself. Spidey diagnoses her Electra Complex in a discreet inner-monologue that is a tour-de-force of Mighty Marvel psychobabble:

Aw, geez. This poor, poor lady. She loved her father so much…too much. His death must have shattered her emotional balance. What her mother obviously wanted her to get…was psychiatric help! But she couldn’t accept that her mom didn’t approve of her being like her father. So she latched onto me as a substitute father! In her own, childlike way...she really does love me!Thus, Michelinie ultimately presents Felicia Hardy as pathetic rather than sinister, “childlike” rather than predatory. The removal of her Cat-mask that accompanies the climactic revelation of the love-shrine she’s built to Spider-Man rather than daddy is designed to underscore this point. Felicia is not a femme fatale after all, but a troubled young woman in need of compassion and psychiatric care.

Yet, this ending is not really much of an improvement on the femme fatale “love story” because all it really does is invert the terms of contempt. “Love” is still feminized, still pathologized, and the hero remains fundamentally “safe” from its temptations. In the end, Spider-Man may show Felicia the “love” she seeks, but it is all in the form of playacting, safely contained within ironic scare-quotes: “Cat… Felicia... I want you to do something for me. I, uh, know some people, some doctors. I’d like you to talk with them. And I promise...‘love’...I’ll see that you get all the help you need.” The story, in short, declaws the Black Cat, but it does not fundamentally undermine the phobic attitude to love (or to women, for that matter) that all too often underwrites the genre. It allows Spider-Man to “care” for Felicia, but only insofar as this affection never makes the hero truly vulnerable or puts his own mastery of the situation at risk.

Yet, this ending is not really much of an improvement on the femme fatale “love story” because all it really does is invert the terms of contempt. “Love” is still feminized, still pathologized, and the hero remains fundamentally “safe” from its temptations. In the end, Spider-Man may show Felicia the “love” she seeks, but it is all in the form of playacting, safely contained within ironic scare-quotes: “Cat… Felicia... I want you to do something for me. I, uh, know some people, some doctors. I’d like you to talk with them. And I promise...‘love’...I’ll see that you get all the help you need.” The story, in short, declaws the Black Cat, but it does not fundamentally undermine the phobic attitude to love (or to women, for that matter) that all too often underwrites the genre. It allows Spider-Man to “care” for Felicia, but only insofar as this affection never makes the hero truly vulnerable or puts his own mastery of the situation at risk. And yet, despite my hesitation over the sketchiness of this comic’s gender politics, I can’t shake the feeling that almost nothing about this analysis rings true when I compare it to my original experience of reading.

I loved this story the first, second, and hundredth time I read it. And what’s more, even though I didn’t grasp the allusiveness of the cover image as fully as I do now, I understood the story inside the comic to be a story about romantic love between Spider-Man and the Black Cat. Most importantly, I understood it to have a happy ending. And (I may be flattering myself here) I understood this happy ending in very different terms than those described above. I understood this ending not to be about pity or power or even compassion. I understood it, rather, to be a love story in the fullest, most mutual sense of that term.

I loved this story the first, second, and hundredth time I read it. And what’s more, even though I didn’t grasp the allusiveness of the cover image as fully as I do now, I understood the story inside the comic to be a story about romantic love between Spider-Man and the Black Cat. Most importantly, I understood it to have a happy ending. And (I may be flattering myself here) I understood this happy ending in very different terms than those described above. I understood this ending not to be about pity or power or even compassion. I understood it, rather, to be a love story in the fullest, most mutual sense of that term.What story did I read, anyway?

The story I read hinges on a subplot between luckless bachelor Peter Parker, who is working as Teaching Assistant at Empire State University, and a female student in his class named Dawn Starr.*

Dawn--blond, curvaceous, and clad head-to-toe in a pink suit--is almost a parody of feminine desirability, and spends most of her panel time throwing herself at Peter, wearing down his resolve not to cross the ethical line that forbids him from dating a student. Peter crumbles under the onslaught of Dawn’s campaign, of course, even allowing himself to believe that “things are looking up for ol’ Petey Parker.” At age eight, I was green enough to believe that this might actually be true.

Dawn--blond, curvaceous, and clad head-to-toe in a pink suit--is almost a parody of feminine desirability, and spends most of her panel time throwing herself at Peter, wearing down his resolve not to cross the ethical line that forbids him from dating a student. Peter crumbles under the onslaught of Dawn’s campaign, of course, even allowing himself to believe that “things are looking up for ol’ Petey Parker.” At age eight, I was green enough to believe that this might actually be true.  But like all Spider-Man stories, it does not deviate from the unwritten law that Peter Parker’s optimism will always be unfounded: Dawn turns out to be an unscrupulous temptress, manipulating Peter so that she can gain access to the science exams he keeps locked in his office. In an ugly scene, late at night, where Peter (as Spider-Man) catches Dawn red-handed at his filing cabinet, our hero comes very close to losing it, shouting, “Lady, in Iran they execute people just for thinking about what I’d like to do to you! But I’ll try to control myself for another five seconds. After which, if you’re still here...!” Dawn flees, and the last four panels are both a portrait of dejection and a blueprint of this issue’s narrative structure.

But like all Spider-Man stories, it does not deviate from the unwritten law that Peter Parker’s optimism will always be unfounded: Dawn turns out to be an unscrupulous temptress, manipulating Peter so that she can gain access to the science exams he keeps locked in his office. In an ugly scene, late at night, where Peter (as Spider-Man) catches Dawn red-handed at his filing cabinet, our hero comes very close to losing it, shouting, “Lady, in Iran they execute people just for thinking about what I’d like to do to you! But I’ll try to control myself for another five seconds. After which, if you’re still here...!” Dawn flees, and the last four panels are both a portrait of dejection and a blueprint of this issue’s narrative structure. They show Peter alone in his office, peeling off his Spider-Man mask and giving in to self pity: “That’s wonderful. The Black Cat is a thief who claims to like me, while Dawn claims to like me, and turns out to be a thief! Let’s face it, Parker, if the world was a tuxedo, you’d be a second-hand jogging shoe! With a broken lace!” But these panels also tell us how to read the rest of the story in a way that subtly redeems the ending, overlaying its condescending fable of masculine rationality and female weakness with an emotional resonance that transforms the meaning of the final pages and pulls our reading experience in a very different direction.

At the heart of this alchemy is the issue’s (and indeed the series’s) presentation of male loneliness and longing as a normal, even integral, component of Peter’s heroism. In fact, I don’t think it would be too much to say that Spider-Man has been, at various points in its history, a romance comic for boys in the guise of an action serial. What makes Spider-Man such a wonderful character is that Peter Parker is inoculated from the so-called “danger” of being “feminized” by love because he is a character that, like Archie Andrews, is defined from the beginning by his desire for intimate relationships with women--a state of desire that is acutely in evidence here.**

At the heart of this alchemy is the issue’s (and indeed the series’s) presentation of male loneliness and longing as a normal, even integral, component of Peter’s heroism. In fact, I don’t think it would be too much to say that Spider-Man has been, at various points in its history, a romance comic for boys in the guise of an action serial. What makes Spider-Man such a wonderful character is that Peter Parker is inoculated from the so-called “danger” of being “feminized” by love because he is a character that, like Archie Andrews, is defined from the beginning by his desire for intimate relationships with women--a state of desire that is acutely in evidence here.**In a more specific way, Peter’s explicit contrasting of Dawn Starr with the Black Cat in his monologue presents these women as inversions of each other and implies that Peter’s relationship with each will be an extension of this reciprocal structure, even he doesn’t realize the full implications of this yet. If Dawn is the prototypical minx, then Felicia must be much more than she appears. The issue as a whole, moreover, confirms this point: Peter’s compassionate embrace of Felicia at the end is an exact inversion of the violent outburst against Dawn that he barely manages to contain. This symmetrical structure is what organizes the issue’s emotional power, a power that makes the ending feel much happier than it actually is.

Of course, Peter is necessarily barred from pursuing a real relationship with the Black Cat by the circumstances of the story. Felcia’s fragile mental health precludes a conventional happy ending, requiring instead that Peter do the decent thing and find help for (rather than satisfaction with) his secret admirer. Yet, because of the contrast between the two women and the story’s symmetrical narrative structure, this anticlimax in no way diminishes the sense of emotional satisfaction the story provides at that moment when Felicia ignites the lamp and reveals to Peter that he is not just a broken lace on the second-hand jogging shoe of life, but has actually been the true object of affection all along!

When I was eight, this panel was my favorite image in the whole comic, and I will address it in more detail below. For now, it is enough to notice that the contrast between the cold empty space of Peter’s office and the warmly lit room of Felicia’s penthouse--a room that is literally overstuffed with the paraphernalia of love--is the culmination of the reciprocal structure we’ve been tracing. The entire story builds towards the emotional impact of this moment (beautifully rendered by Keith Pollard and Jim Mooney) in which Peter Parker discovers that he is not as alone as he initially thought. What he discovers may not technically be “love,” but in that instant, it sure feels like it.

When I was eight, this panel was my favorite image in the whole comic, and I will address it in more detail below. For now, it is enough to notice that the contrast between the cold empty space of Peter’s office and the warmly lit room of Felicia’s penthouse--a room that is literally overstuffed with the paraphernalia of love--is the culmination of the reciprocal structure we’ve been tracing. The entire story builds towards the emotional impact of this moment (beautifully rendered by Keith Pollard and Jim Mooney) in which Peter Parker discovers that he is not as alone as he initially thought. What he discovers may not technically be “love,” but in that instant, it sure feels like it.Some time ago, I wrote about the peculiar childhood pleasure of reading comic books in fragmented sections or “blocks,” rather than as single coherent narratives. My experience of this issue as a real love story is partially related to this selective practice of reading. As I argued in that earlier piece, one consequence of reading in blocks is the possibility of reading somewhat--though never entirely--against the grain of the story’s overtly intended meaning. In this case, the revelation of the room filled with romantic artifacts that the Black Cat has stolen for Peter assumes an infinitely more ambiguous meaning than the one Spider-Man himself will assign to it in his neat Freudian wrap-up on the following page.

Despite the diagnosis Spidey goes on to provide, the Black Cat’s love shrine does not feel pathological, nor does it even feel inappropriate. Or rather, it does feel like both of these things, but only to the extent that love itself feels this way. The “shrine” to Spider-Man might be “sick” in the context of the story, but emotionally, we can recognize it as no less than what the lonely, noble, long-suffering Peter Parker in all of us deserves. It is, quite simply, the universal need to loved completely and unreservedly.

Is the symbolic satisfaction of desire represented by the Black Cat’s Spider-Man portrait gallery “narcissistic”? Yes, clearly. Yet all love, one suspects, contains a strong element of narcissism, at least initially. The conventional wisdom that opposites attract is only partly true, since we so often love not otherness per se, but that idealized image of what we might like to be, reflected in some other, who may or may not be the true bearer of this seemingly perfect self. And of course we are all susceptible to the kind of worship that Felicia bestows on Spider-Man. It’s easy to interpret this scene cynically, and to dismiss it as a narcissistic masculine fantasy of the “perfect woman,” but the trope of the lover’s worship of their object should not be so summarily dismissed, for it is only as sinister as the context allows. As I have tried to show here, the context of this “shrine” is richer and more complex than it first appears.

The relation between love and narcissism is obviously a more complicated question than I can adequately address here. My ultimate point is simply that the language of pathology that frames and “makes sense of” the Black Cat’s behaviour in this scene of adoration is not alien from how we think about and attempt to characterize the experience of loving another person. Often, it seems like the only available language in which we can properly convey the excessiveness of this lawless emotion. It’s not a coincidence that unrequited desire earns the name “love sickness”...

What this means, I think, is that The Amazing Spider-Man #205 actually tells two stories about love that are overlapping and not entirely compatible. The first story is a very childish story that is afraid of love and is at pains to ward it off, embodying it in the hackneyed form of the madwoman, the stalker, the obsessive. The second story is more adult. It stems from the peculiarity of a “romantic” male protagonist who is not the superior but the equal of his love-struck tormentor. Moreover, it effectively reinterprets the elements of the first story according to an emotional logic that recasts the literal association of love with “mental illness” as a metaphor for love sickness and desire. The implications of this second story are subtly played out beneath and behind the events of the first story’s overtly more conservative meaning, haunting this story like the ghost of a story that was almost, but not quite, written.

III: Objects

If we allow ourselves the luxury of returning to childhood habits of reading, and appreciate the story for its emotional rather than its literal truth, we might therefore find that Michelinie has written a profound meditation on the nature of love in the unlikely form of a Spider-Man comic. It is a vision of love that is remarkable, I think, because it expresses itself not through narrative, but through objects.

A small golden statue of “The Two Lovers.” The Eye of Eros Diamond. A one-of-a-kind wax recording of Caruso singing a love aria. The Helen Epistle--“the only known love letter written to Paris by Helen of Troy.” These romantic artifacts that the Black Cat steals are what make this story special.

A small golden statue of “The Two Lovers.” The Eye of Eros Diamond. A one-of-a-kind wax recording of Caruso singing a love aria. The Helen Epistle--“the only known love letter written to Paris by Helen of Troy.” These romantic artifacts that the Black Cat steals are what make this story special. I have already suggested that if we read the narrative symbolically rather than literally, the Black Cat is not a madwoman, but an archetypal lover. She is also, I think, the bearer of a certain “philosophy” of love. What she shows us, through these objects, is the anatomy of a lover’s discourse: a description of its features and its strange paradoxical character.

The objects themselves, Felicia tells Spidey, are “the most valuable romantic symbols in the country,” and like all symbols of love they are impossible objects in the sense that they stand in for an experience that, by its very nature, is excessive, formless, and resistant to representation. This is why they are also, in my own reading experience, blocks of supreme narrative intensity. The panels in which these objects appear are supercharged with meaning. The eye goes to them, and lingers there. What do they symbolize about love?

Value, most obviously. And like the value of the loved one in the eyes of the lover, their value is infinite and springs from their utter singularity. The “one-of-a-kind” wax recording of the love aria defines the nature of all four “artifacts” and the emotion they represent. (The very word “artifact” suggests something rare and precious, something fragile and unique salvaged from destruction, the remnant of some earlier golden age. Edenic artifacts, perhaps.) The Helen Epistle is “the only known love letter” from the woman whose face launched a thousand ships to her Greek warrior-lover. The mere fact of their names signifies the uniqueness of the “Eye of Eros” diamond and the erotic sculpture of the “Two Lovers.”

And yet, despite their “uniqueness” and “singularity,” these love artifacts exceed their original contexts. Helen’s love letter is no longer a private communication but a public symbol. These objects have become “collectible.” They circulate, both legitimately and illegitimately. They are displayed, hoarded, borrowed, stolen. And of course, it is only the true lover who steals, liberating these objects from the museum or the private collection, making them circulate, making them mean something again, reconnecting them with the potency of their original purpose, but for her own ends. This is the paradox: that the lover can only speak of love on the condition that she steals the “language” in which to do so. Her unique, singular desire can only be spoken with a borrowed tongue, with clichés, with “the most valuable romantic symbols in the country.”

And yet, despite their “uniqueness” and “singularity,” these love artifacts exceed their original contexts. Helen’s love letter is no longer a private communication but a public symbol. These objects have become “collectible.” They circulate, both legitimately and illegitimately. They are displayed, hoarded, borrowed, stolen. And of course, it is only the true lover who steals, liberating these objects from the museum or the private collection, making them circulate, making them mean something again, reconnecting them with the potency of their original purpose, but for her own ends. This is the paradox: that the lover can only speak of love on the condition that she steals the “language” in which to do so. Her unique, singular desire can only be spoken with a borrowed tongue, with clichés, with “the most valuable romantic symbols in the country.” That these symbols will be inadequate to describing the lover’s desire is obvious, and no one knows this better than the Black Cat: it’s why she steals not one object, but many. And also why her communication with Spider-Man is so circuitous. As if she is holding off until her message is perfect, trying to find the one word that will say enough, or to plug, through sheer numbers, that gap of meaning that can never fully be sealed. That tiny pinhole through which “what she really wanted to say” escapes. The Black Cat’s logic, in other words is not as absurd as it sounds: “I set about stealing the most valuable romantic symbols in the country just to show what you mean to me and now we love each other, don’t we?” This is the confession and the secret wish of every prospective lover: the right words are a magic charm, and if I find them, it will be true.

The meditations these objects make possible all refer to a philosophy of love that is, to say the least, extreme. It is consistent with the violent, overwhelming, cataclysmic image of love presented on the cover.

What I love about this comic, however, is that its final image points equally to another, more sustainable state of love: not the frenzy of “love sickness,” but the patient loving mutuality of another, later stage. In this last image Keith Pollard frames Spider-Man and the Black Cat, walking arm-in-arm like a loving couple, between two of the story’s most significant symbolic objects. The golden statue of the “Two Lovers” and the “Eye of Eros” diamond (miscolored to look like a ruby) loom large in foreground, magnified to giant size by the composition of the panel. The placement of these objects offers a final way of contextualizing the meaning of this strange “romance.”

What I love about this comic, however, is that its final image points equally to another, more sustainable state of love: not the frenzy of “love sickness,” but the patient loving mutuality of another, later stage. In this last image Keith Pollard frames Spider-Man and the Black Cat, walking arm-in-arm like a loving couple, between two of the story’s most significant symbolic objects. The golden statue of the “Two Lovers” and the “Eye of Eros” diamond (miscolored to look like a ruby) loom large in foreground, magnified to giant size by the composition of the panel. The placement of these objects offers a final way of contextualizing the meaning of this strange “romance.”These two objects--the erotic statue and the pure diamond--symbolize complementary states of love which, in another century, might have been characterized as “earthly” and “divine,” “bodily” and “spiritual,” or “fleshly” and “ideal.” Since I don’t like the hierarchy these oppositions imply (what’s wrong with “earthly” love, after all?), I read them, willfully, as symbols of body and mind, of physical and mental love. This is an artificial separation to be sure, but one which has the virtue of clarifying the significance of the embrace between Peter and Felicia that takes place literally “between” these two forms of love.

When I was eight, this panel was quite simply a happy ending. Two lovers heading off into the future. When I look at this image now, I see something more subtle, something that only a more mature person--Michelinie or Pollard--would be capable of suggesting: two people who are walking as equals, partners in a relationship that navigates the only superficially distinct regions of body and mind, passion and judgment, love and friendship. This is an image of love that I could grow to idealize.

In my own, clearly idiosyncratic reading of this comic, the final panel does something magical: its composition transposes Spider-Man and the Black Cat onto the plane of objects. The couple seems literally to have joined the ranks of the very romantic artifacts that the Black Cat so painstakingly assembled. For me at least, this “transformation” is emblematic of what this story does. In my own private history, this story has become one of those borrowed or stolen artifacts through which it becomes possible to talk about the thing that baffles me. It has become, like Helen’s letter to Paris, or the wax recording of Caruso’s aria, the basis for a borrowed yet paradoxically very personal discourse on the elusive mysteries of the human heart.

Notes

Notes* David Michelinie was evidently a fan of the Legion of Superheroes, or perhaps harbored a secret dislike for Dale Messick.

** If you’re still not convinced, read this inspired post on Spider-Man, love, and intersubjectivity by David Fiore at Motime Like the Present. I’ve plundered its insights shamelessly--and then buried the evidence in footnotes. Hi Dave!

9 comments:

Brilliant read.

I was wondering, as I do when I read most critical readings of different books, how you can tell if the artist or writer actually meant to instill those ideas or feelings within the reader or if they were some kind of happy accident. A subconcious thought that works it's way into whatever their current project is. I don't think that's a question that can be answered, but I still wonder...

Hi Shane--thanks! And gee, ask a small question, why don'tcha!! I started writing a reply but it soon got a bit...out of control, shall we say. I'm going to finish it up later and post it as its own thing in a day or so. Suffice it to say for now that "authorial intention" is a very complicated issue! Thanks for the question.

I look forward to hearing your thoughts because I know I've thought about it before and I don't have an answer.

so good!

I loved the way you used the Dawn subplot to complicate the reading (isn't that what subplots are for?)

will you be following up on this with some analysis of the Black Cat's (at Roger Stern's behest) return two years later? I haven't read any of these in a long time... (and I confess that--although I've ranted a great deal about Spidr-Man and romance--I've never given much thought to Felicia Hardy's place in the story!)

Dave

Thanks, Dave! No plans for more Black Cat right now, but after reading your comment I scurried off to the Big Comic Book Database to see which issues you were talking about (226-27 by the look of things). Truth be told, I wasn't reading Spider-Man with anything resembling consistency in the early 80s, but boy do those issues ever look great (w/ John Romtia Jr. art no less). Roger Stern's tenure on the Avengers remains my all-time favorite era of that title, so I'll definitely go hunting for his ASM issues.

A lot of their relationship occured in Spectacular Spider-man as well, with it's culmination around #100 or so.

I remember reading this in Olshevsky's Index series when I was just a little older than you were, finding the issue. The art adds so much, which is the point of comics, after all.

I wonder sometimes how much of this analysis occurs to the creators as they sit to compose these juvenile lit stories?

I enjoyed the cover analysis most of all; it's a Roeg specialty!

ASM #194 came in a kit of drawing supplies, when I was six or seven, and that is, of course, Felicia's first appearance. This was all somewhere in my mind, I think, when I completed this story, "The Electric Thief". http://welltoldtales.com/short-stories/c-lue-disharoon/1/20/10/electric-thief If you read this and like it, or have something to allow, please contact me? It's quite good, I'm told.

You mean the Reagan that increased spending by 191%? What's this to do with ASM #205, anyway? Looking forward to Jim deleting non-relevant posts.

Post a Comment