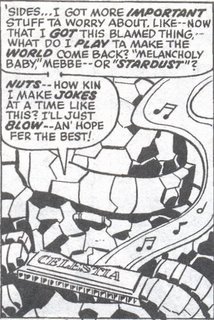

Everything that is beautiful and profound and human about Steve Gerber’s melancholy aesthetic is summed up in this exceptional panel from Marvel Two-In-One #7 drawn by Sal Buscema: The world has just been destroyed in a most improbable way: down-and-out alcoholic Alvin Denton (a one-time lawyer whose wife was killed in a car accident and whose daughter ran off with cult) has just blown a tune on the mysterious “Celestia” harmonica, an instrument of fate that “plays the notes of destiny.” Alvin’s cataclysmic playing accelerates his own self-destruction, but it also generalizes the calamity by magically literalizing the truism that the drunkard is “destined to see his whole world destroyed.” The harmonica thus becomes a sort of final blast of the divine trumpet, unmaking the earth and setting Alvin, his “daughter” Valkyrie, the Enchantress, her henchman the Executioner, and the ever-lovin’ blue-eyed Thing adrift, “floating in a kind of un-space amid the pieces of Alvin’s shattered existence.” After a brief skirmish with the Enchantress and the Executioner, it is the Thing who takes up the harmonica called “Celestia” and contemplates which song will best remake the universe.

The world has just been destroyed in a most improbable way: down-and-out alcoholic Alvin Denton (a one-time lawyer whose wife was killed in a car accident and whose daughter ran off with cult) has just blown a tune on the mysterious “Celestia” harmonica, an instrument of fate that “plays the notes of destiny.” Alvin’s cataclysmic playing accelerates his own self-destruction, but it also generalizes the calamity by magically literalizing the truism that the drunkard is “destined to see his whole world destroyed.” The harmonica thus becomes a sort of final blast of the divine trumpet, unmaking the earth and setting Alvin, his “daughter” Valkyrie, the Enchantress, her henchman the Executioner, and the ever-lovin’ blue-eyed Thing adrift, “floating in a kind of un-space amid the pieces of Alvin’s shattered existence.” After a brief skirmish with the Enchantress and the Executioner, it is the Thing who takes up the harmonica called “Celestia” and contemplates which song will best remake the universe.

This moving panel is Gerber’s Creation scene, and it is a précis of his meditation on what it means to be human in a world where, as Sartre once said, existence precedes essence.

Would Gerber call himself an existentialist? Can his work be characterized so narrowly? Perhaps not. I freely confess that I have not read enough of it to say, but smart people who know far more about Gerber than I do seem to think that it has existentialist dimensions, so the connection is at least worth exploring further.

Consider the resonance between the small panel from Marvel Two-In-One #7 (above) and this passage from Existentialism in which Sartre explains his famous dictum by first defining “man” in terms of divinely created essence and then discarding this vision of being for an existential one:

When we conceive God as the Creator, He is generally thought of as a superior sort of artisan.... Thus, the individual man is the realization of a certain concept of divine intelligence.... [Conversely,] atheistic existentialism, which I represent,…states that if God does not exist, there is at least one being in whom existence precedes essence, a being who exists before he can be defined by any concept, and that being is man, or, as Heidegger says, human reality. What is meant here by saying that existence precedes essence? It means that, first of all, man exists, turns up, appears on the scene, and, only afterwards, defines himself. If man, as the existentialist conceives him, is indefinable, it is because at first he is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be. Thus, there is no human nature, since there is no God to conceive it. Not only is man what he conceives himself to be, but he is also only what he wills himself to be after his thrust toward existence. (389-90)Sartre calls this idea, that “Man is nothing else but what he makes of himself,” “the first principle of existentialism,” and I cannot help speculating that it is also a sort of “first principle” for Gerber’s own philosophical, searching, often absurdist, spandex melodramas.

“What do I play ta make the world come back? ‘Melancholy Baby,’ mebbe—or ‘Stardust’? Nuts—how kin I make jokes at a time like this? I’ll just blow—an’ hope fer the best.” What is this but a sly parody of metaphysical thinking? What is this but an existentialist creation scene in which transcendental tropes like the divine breath of creation and the music of the spheres are recast as melancholy human music played on an instrument whose haunting wail is synonymous with the complex emotional register of the blues? Instead of a world of essences, created by God or some other transcendental principle, Gerber gives us a world of existence, created by a man and symbolically (re)created here by Marvel’s greatest existentialist character, the Thing. The rocky, heavy, earth-bound Thing, as Gerber presents him, is an exaggerated, defamiliarized image of humanity grasped as pure existence, without God, without any transcendent consolations whatsoever. If Sartre’s famous dictum that “existence precedes essence” entails the acknowledgement that man creates God, not vice versa, then this scene, in which the Thing takes God’s place to recreate the world in his own flawed and finite image, becomes the embodiment of that difficult existential dictum. It is a “minor” creation scene whose very off-handedness (it is literally one tiny panel on an eight-panel page) is precisely the point. No Kirbyesque cosmic grandeur here. No Eternity, no Celestials, only “Celestia,” stamped on the tin-plating of a dime-store harmonica. And yet, the grandeur and significance of the act is in many ways more profound than the dazzling effulgence of Kirby’s cosmic fantasmagoria.

What makes this panel so moving is that we do not see the Thing’s eyes. They are downcast and hidden by his enormous, craggy brow. This is the bent head of contemplation, responsibility, consciousness—what Sartre calls “anguish”: what is felt by “the man who involves himself and who realizes that he is not only the person he chooses to be, but also a law-maker who is, at the same time, choosing all mankind as well as himself, [and thus] cannot help escape the feeling of his total and deep responsibility” (Sartre 391). But the bent head of the Thing’s anguish is balanced against the musical line that rises from the harmonica, those few sad notes that instantly remake the world as a place of absurd, often painful, but still potentially beautiful habitation. The emotional texture of this perfect panel—for which much credit must go to Sal Buscema—is signified by the harmonica itself: a commonplace instrument inscribed with “celestial” significance.

What makes this panel so moving is that we do not see the Thing’s eyes. They are downcast and hidden by his enormous, craggy brow. This is the bent head of contemplation, responsibility, consciousness—what Sartre calls “anguish”: what is felt by “the man who involves himself and who realizes that he is not only the person he chooses to be, but also a law-maker who is, at the same time, choosing all mankind as well as himself, [and thus] cannot help escape the feeling of his total and deep responsibility” (Sartre 391). But the bent head of the Thing’s anguish is balanced against the musical line that rises from the harmonica, those few sad notes that instantly remake the world as a place of absurd, often painful, but still potentially beautiful habitation. The emotional texture of this perfect panel—for which much credit must go to Sal Buscema—is signified by the harmonica itself: a commonplace instrument inscribed with “celestial” significance.The sublimity of this panel is inseparable from the symbolism of the Thing himself. To be human in an existentialist universe is to be a Thing. This is what Albert Camus taught us in his famous allegory, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” where Sisyphus, plaything of sadistic gods, another brute compelled to wrestle with rocks, becomes “the absurd hero,” a prototype of existentialist consciousness—in short, a prototype for the Thing himself:

The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock back to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight.... [O]ne sees merely the whole effort of a body straining to raise the huge stone, to roll it and push it up a slope a hundred times over; one sees the face screwed up, the cheek tight against the stone, the shoulder bracing the clay-covered mass, the foot wedging it, the fresh start with arms outstretched, the wholly human security of two earth-clotted hands. At the very end of his long effort measured by skyless space and time without depth, the purpose is achieved. Then Sisyphus watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward that lower world when he will have to push it up again toward the summit. He goes back down to the plain.Gerber’s Thing is not “scornful” of fate so much as he is glumly prepared to endure it, but the sense of tragedy that surrounds his character stems precisely from his consciousness of the absurdity and interminability of his suffering. Yet, for Gerber, as for Camus, this “tragic” existential consciousness isn’t cause for despair. The Thing in question may be Ben Grimm, but he is also “ever-lovin’” and “blue-eyed.” As Camus puts it in a moment of startling reversal,

It is during that return, that pause, that Sisyphus interests me. A face that toils so close to stones is already stone itself! I see that man going back down with a heavy yet measured step towards the torment of which he will never know the end. That hour like a breathing-space which returns as surely as his suffering, that is the hour of consciousness. At each of those moments when he leaves the heights and gradually sinks toward the lairs of the gods, he is superior to his fate. He is stronger than his rock.

If this myth is tragic, that is because its hero is conscious. Where would his torture be, indeed, if at every step the hope of succeeding upheld him? The workman of today works every day in his life at the same tasks, and this fate is no less absurd. But it is tragic only at the rare moments when it becomes conscious. Sisyphus, proletarian of the gods, powerless and rebellious, knows the whole extent of his wretched condition: it is what he thinks of during his descent. The lucidity that was to constitute his torture at the same time crowns his victory. There is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn. (407-08)

If the descent [of Sisyphus] is sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much.... One does not discover the absurd without being temped to write a manual of happiness.... Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable. (408)In Gerber’s existentialist creation scene, the Thing is a Sisyphian creator-hero, poised precisely between melancholy (what Camus calls “the victory of the rock”) and the astonishing claim that “One must imagine Sisyphus happy” (Camus 409). Confronted with the oblivion of “un-space,” nothingness, the Thing wonders: “What do I play ta make the world come back? Melancholy Baby, mebbe—or Stardust?” Read the lyrics to these songs. They are melancholy and nostalgic, but something else too:

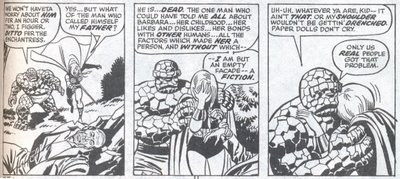

You shouldn’t grieve; try and believeSet in the context of Gerber’s existentialist creation, these songs, especially George A. Norton and Ernie Burnett’s “My Melancholy Baby,” are something like the “manual of happiness” to which Camus enigmatically alludes. They are blueprints for a mode of living authentically, consciously, in a world where nothing but our existence is pre-given, where value must be made, and where—for better or worse—anything is possible. “Be of good cheer; smile through your tears; / When you’re sad it makes me feel the same as you”: this is the magnificent ethical vision of Gerber’s committed existentialism. Look a little further down the page from the scene in which Ben Grimm’s human music remakes “not the best” world but “the world as we know it.” You will see these three panels in which Valkyrie realizes that the one man who could have provided her with the “truth” of her identity is now forever out of reach:

Life is always sunshine when the heart beats true.

Be of good cheer; smile through your tears;

When you’re sad it makes me feel the same as you.

How else could an existential creation end except with a discovery of the death of the Father? Gerber’s story allegorizes the frustrated hope for easy answers and “revelations” about identity and being. It gives us only Val’s confrontation with the blankness of her own identity and her dawning consciousness that she, like Grimm, is a human thing “condemned to be free” (Sartre 393). That is, she is condemned to, but also liberated by, an existence without essence: empty, except for what she chooses to become. It ends with Ben’s hard-boiled compassion, a gruff rephrasing of those tragic, beautiful, affirmative lines from “Melancholy Baby”: “Whatever ya are, kid—it ain’t that. Or my shoulder wouldn’t be getting’ drenched. Paper dolls don’t cry. Only us real people got that problem.”

How else could an existential creation end except with a discovery of the death of the Father? Gerber’s story allegorizes the frustrated hope for easy answers and “revelations” about identity and being. It gives us only Val’s confrontation with the blankness of her own identity and her dawning consciousness that she, like Grimm, is a human thing “condemned to be free” (Sartre 393). That is, she is condemned to, but also liberated by, an existence without essence: empty, except for what she chooses to become. It ends with Ben’s hard-boiled compassion, a gruff rephrasing of those tragic, beautiful, affirmative lines from “Melancholy Baby”: “Whatever ya are, kid—it ain’t that. Or my shoulder wouldn’t be getting’ drenched. Paper dolls don’t cry. Only us real people got that problem.” This statement is more paradoxical (and joyful) than it seems because, of course, Val and Ben really are “paper dolls” in at least two senses. As comic book characters, they are literally “fiction[s]”—in this sense, Val is right to lament that she is “an empty façade, a fiction,” even if she does not grasp the metafictional significance of what she is saying. But Val is right in another, profounder sense too if we take her anguish over being “an empty façade, a fiction” as a moment of genuine existentialist consciousness—consciousness of a world without essences, a world not designed and governed by some divine “father.” “Fiction,” in this sense, simply designates an identity that has become unmoored from the consolations and pseudo-certainties of metaphysics, and in this sense Val and the Thing are fictions, are “paper dolls”—just as we all are in an existentialist night. The exquisite irony of this ending is that paper dolls do cry, despite what Ben says to make Val feel “human.” In other words, this concluding sequence appears to oppose “paper dolls” to “real people,” but it actually does something far more interesting: it redefines what it means to be human in a single stroke by collapsing the distinction between “paper dolls” and “real people,” making it untenable. This is the deconstructive moment of Gerber’s “Two-In-One” where the shift from metaphysics to existentialism that had been condensed in the panel of parodic creation (the Thing and his harmonica) is unpacked and dramatized as a minor, and deeply moving existentialist fable in which the Thing now plays his fully human role instead of playing a parody of God.

For me, what accounts for the incredible pathos of this ending is the paradoxical nature of Ben’s consoling remark. Val’s tears affirm the most profound truth of Gerber’s universe: that to be human is to suffer. But Gerber’s genius is to make this tragic truth its own consolation, for it is precisely Val’s suffering that affirms her humanity at the very moment that she sinks into anguish at not having a metaphysically-grounded identity. There’s something strangely uplifting about this melancholy ending. Camus:

If the descent [of Sisyphus] is sometimes performed in sorrow, it can also take place in joy. This word is not too much....One does not discover the absurd without being temped to write a manual of happiness....Happiness and the absurd are two sons of the same earth. They are inseparable....To this, Gerber might add that the difficult happiness that accompanies existential freedom flourishes not in the isolated, alienated figure of Sisyphus, the “absurdist hero,” but in communities of other such “real people” whose marginality has provoked them to similar struggle and reward. The Defenders are, of course, a very prominent expression of this communal impulse in Gerber’s work, and as plok says in his fascinating inaugural "Seven Soldiers of Steve" post, Gerber’s Defenders valued community in a way that Englehart’s did not:

I leave Sisyphus at the foot of the mountain! One always finds one’s burden again. But Sisyphus teaches the higher fidelity that negates the gods and raises rocks. He too concludes that all is well. This universe henceforth without a master seems to him neither sterile nor futile. Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world. The struggle itself towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. (408-409)

[For Englehart’s Defenders], being a “non-team” was primarily a way of acknowledging that they each preferred their own individual, solitary company to that of society’s, and they were all secure enough in their own skins that they never apologized for preferring to be strangers.As even these few remarks indicate, plok’s analysis of the Defenders as a “meditation on life outside the mainstream, but not all the way outside the mainstream,” takes the notion of a superheroic community of misfits who “wanted their roles to fit in with their lives, not their lives with their roles” in the direction of the politically engaged consciousness that is central to Gerber’s stories, including the stories in Marvel Two-In-One that I haven’t even begun to analyze here. I agree wholeheartedly with plok’s reading; all I have been trying to sketch out are some preliminary thoughts about the existential subtext of Gerber’s political project—particularly his fascination with marginality and questions of responsibility and social justice. It isn’t for nothing that the issue of Marvel Two-In-One I’ve been speaking about ends with a strange embrace, with tears on a compassionate but unyielding shoulder of rock. It ends, in other words, with a strange human community—the Thing and Val—an odd-couple of the type that Marvel Two-In-One, especially Gerber’s, will specialize in. Indeed, Gerber’s stories in Marvel Two-In-One (as the book’s title and concept suggest) are really all studies of the strange community motif that is not just a consolation but (I suspect) a genuine political goal. In a future essay I want to explore how, in Gerber’s work in these issues of MTIO, the strange community emerges as a vision that is at once philosophical, ethical, and political: democracy, or perhaps, “America” as non-team.

Gerber’s Defenders, though, were different. They wanted to fit in and find their place as much as their previous iterations wanted nothing of the kind: Gerber’s Valkyrie was less the warrior-woman and more the ingenue, the foundling abandoned on identity’s doorstep; Nighthawk (introduced to the team by - who else? - Len Wein, who it must be noted was the one who instituted this shift to a friendlier “non-team,” that was more a group of friends who all hung out together than a pack of loners jammed together by necessity, or an organization with code-names and signal devices) was a man trapped by his own conditions of past and class and error, who wanted nothing more than to make a fresh start, even if to do so made him a less confident, less effective person; the Hulk was more a misunderstood child than a threatening monster; and Dr. Strange was (as Kurt Busiek put it in his Defenders run) a warm and avuncular presence, suffused with calm and inner peace, rather than the sometimes-impatient, work-obsessed prima donna he had often been portrayed as before. Each of these characters remained as potent, and potently symbolic, as they had been earlier; but because their attitude to their world had changed, what they had to do in it changed as well. They wanted to fit in, yes: but on their own terms and in their own places, instead of merely taking up desultory roles or niches at the centre, where the other superheroes lived. Because they wanted their roles to fit in with their lives, not their lives with their roles.

In the context of such utopian yearnings, the fact that existential themes often take the form of melancholy or despair is not surprising—such expressions are signs, perhaps, of the Sisyphian difficulty of achieving the sort of social transformation to which the stories themselves repeatedly allude. But Gerber’s existentialism is not just a cry of anguish. As I’ve been suggesting here, it is also the precondition of a kind of grim (Grimm?) optimism: the strange happiness of Sisyphus who struggles with the anguish of his own freedom and the awesome responsibility that such radical freedom entails. This is the happiness of Ben Grimm (a cipher for Gerber himself) who must play the world into existence on a cheap harmonica. And most of all, it is the painfully human happiness that is presented to us like a gift in that memorable image of Valkyrie wrapped in the Thing’s embrace: it is the happiness of knowing why paper dolls don’t cry but also why they do, of what it means to be “real people,” and of the strange communities that such difficult knowledge makes possible.

Works Cited

Camus, Albert. "The Myth of Sisyphus." Trans. Justin O'Brien. Casebook on Existentialism 2. Ed. William V. Spanos. New York: Harper & Row, 1976. 406-409.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. "Existentialism." Trans. Bernard Fretchman. Casebook on Existentialism 2. Ed. William V. Spanos. New York: Harper & Row, 1976. 387-406.

9 comments:

Wow. You knocked the ball right of the park again. Even though I disagree at times with your philosophic viewpoint while discussing these texts, your acumen and your brilliant insights always win me over in the end.

What Benjamin and plok said. Just...wow.

Thanks, friends! And thanks especially to plok for getting the ball rolling on this mad Seven Soldiers of Steve business in the first place. I've already learned tons from the other contributors--and I haven't even read them all yet... I also wanted to mention Disintegrating Clone's wonderful essays on Gerber's Man-Thing and Howard the Duck over on Nobody Laughs at Mister Fish. In addition to plok's inaugural post and Thomas's inspired analysis of Gerber's Daredevil over on plok's site, I reread Disintegrating Clone's essays before writing my own piece, as they were my very first introduction to Gerber's work. Now that I'm done, I'm looking forward to catching up on the posts by Sean Kleefeld and RAB, as well as plok's other posts. In fact, I think I'm going to do that right now!

Jim, this is fantastic. I'm a Sartre fan, but I did not see the wonderful parallels you've teased out.

You have a trait I have to recognize: the gift of meditation and contemplation. To lift one or two panels out of a series of hundreds (and in black and white, no less!) and evaluate them for their emotional and philosophical content is marvelous.

Hi gorjus, thanks for saying that. Sometimes I'm not sure if it's a gift or just a mild touch of brain fever (seriously!). There is something deeply satisfying about just...looking at one thing, though, that's for sure. But the flip-side is that I sometimes have trouble seeing the forest for the trees!

Well, in this situation--the forest may be terrible. Seriously--the Thing and the Defenders. People look to Alan Moore for philosophical turns (or, depending on your views--self-involved new age quackery), but back in that time period it was much hard to "write smart."

Gerber certainly snuck some stuff in there, but I often see just the trees--mediocre 70's art, an often heavy-handed story, characters that I'm meh about. The secret is that there are gems strewn about.

plok - thanks so much for taking the time to fill out the conclusion of the story--this was all news to me, and extremely interesting, particularly Doc's comment that "There is much to despair at here...but also cause for great rejoicing," which could practically have been lifted from Camus's "The Myth of Sisyphus"! Existentialism was "in the air" at that time, of course, but it would be fascinating to know what books were on Gerber's nightstand in 1974 all the same.

There's something very interesting going on with the way that Gerber is fooling around with "fate" and "destiny" in the issue I was talking about that seems to extend into Gerber's Defenders run too: the notion that destiny is in one sense "set" but in another sense not. (This is what the paradox of the disruptive substitution of the Thing for the Hulk suggests to me, at any rate.) It's all probably just a side-effect of "trash-culture" storytelling, but it does have a curious resonance with the extremely complicated (and paradoxical) way that terms like "fate" and "destiny" are deployed in existentialist thought (or Nietzsche, for that matter) where they obviously do not signify "divine" constraint in the more classical sense. Something to dig at in future, perhaps.

gorjus - on the point of "gems" in "trash culture" that you and plok bring up, I've been approaching it as if these gems have not been randomly scattered but actually condense themes that already inform the stories as a whole--albeit in less precise (less crystaline) ways. I always find that reading trash-culture is such a weird process because until you find a gem, what you're reading really can feel like trash. (Don't be fooled kids! Comics ain't all about Sartre and Derrida!) But then you find a gem, and everything looks different--well, maybe not everything, but some of the goofier parts of the action can suddenly take on a kind of faint glimmer from the light thrown off by those gem-like moments. The reason for this, I think, is not simply due to the viewer's change in perception, but because the goofy story has been informed all along by those deeper impulses that ultimately find (nearly) explicit expression in the gem-like moments. Of course, this isn't to say that the gem is "really" shining at us from a stunning setting. It is set in "trash"--but trash that gleams a little when you polish it. (How's that for a pointless display of tortured metaphors?) It would be interesting (if one had the time) to compare the proportion of gems to faintly gleaming trash to real trash in the stories of a number of writers from this (or any)period. Fruitless, probably, but interesting!

Oh, and plok - I have to add Marvel's Essential edition of The Defenders to my pile of comics tomorrow--I'm dying to get a look at that story now!

I love this; existentialism has a way of returning to the fore of my thoughts, and I read much of this aloud to my wife, capable as always of analytical rejoinders. I went back to the Defenders (and a completed FF story, "the Vanishing Wave") to create a pastiche fiction aligned with my novel. These viewpoints have been my only guide to Englehart/Gerber era issues just yet, but the story they tell alongside the commentary is evocative, maybe without some of the limitations that plague their 35 year old counterparts. Part two of two ("Remus Sharptooth Regrets...!")is in my stack of five stories emerging bit by bit from my pen, and this is the grist that restores me when burn-out makes angst of my efforts towards memorable work enjoyed by others.

SO well-written, I had to come back...weird as heck I named a character "Celestia Englehart" almost four years ago...some things!

My experiment related to Gerber's going well, in my stories...well, I don't know, what say thee?

I love the way your writing puts together 1) the story at hand, illustrated in my mind 2) the feel of those times, inasmuch as i can imagine it 3) serious thought I've explored before, with subject matter that's brought me such joy...really brought me out of the closet about my love of comics; love turning non-comics readers on through the quality of the ideas. I'm so into the tone of your writing voice; you, Plok, and Jason Powell over at REMARKABLE are my heroes and companions, xxx so many smart, funny respondents, too

Post a Comment