Better late than never, right Sean? I can’t tell you how tempted I was by King Solomon’s Frogs, but in the end, I have to agree with plok and go with Ben Grimm. This will come as no surprise, I’m sure, since I’ve waxed poetic about the pathos, profundity, and—heck yeah—perfection of Kirby’s great existential hero before.

The idea of a creature composed of living rock is one of humankind’s oldest myths, but Kirby gives this myth its most viscerally human embodiment with one brilliant design feature: the brow. Yes, the orange rocks are essential, but it is the craggy brow shading Ben’s mournful baby-blues that creates a visual metaphor of the character’s extreme vulnerability and gives this pop version of Frankenstein’s Monster the true spark of life. And let’s not forget that Ben Grimm’s connection to Mary Shelley’s monstrous Adam (or is that Eve? or Satan?) extends beyond a visual referencing of the Boris Karloff movie version: Shelley’s original alienated Monster is, in many ways, the existentialist precursor to Grimm as well.

Additionally exciting, I think, is the way the Thing design so successfully sublimates Kirby’s primitivism. The astonishing modernist vitality that Kirby cannot help imparting to everything he draws achieves something unique here: in contrast to his more overtly thematized designs, the Thing is a truly modern primitive, and this means that he uncannily embodies an emotional intensity that (politically incorrect though it now is) modernist art routinely associated with “pre-modern” cultures. The Thing’s living rocky hide makes him a humanized version of the “primitive art” that was in many ways at the heart of Kirby’s own style. That Kirby himself was a stout figure gives Ben Grimm the additional savour of a self-portrait.

The real shame is that Marvel seems unable to imagine a meaningful place for its most adult character in its current universe. Is it a coincidence that the Thing left the FF just as Civil War began? I don’t think so; perhaps he found the whole debacle as depressing as I do. May his exile at least be short-lived.

Monday, November 27, 2006

Wednesday, November 22, 2006

Sunday, November 12, 2006

Double Articulation Digest #2

Doctor Strange: The Oath #1-2 – There’s still time. If you hesitated about buying the first issue because the cover logo was so inexplicably ugly, it’s probably not too late to reconsider. My advice? Just suck it up and take the plunge. Yes, the logo is hideous; but if you turn the page quickly, you’ll forget it in no time. Brian K. Vaughan and Marcos Martin are outdoing themselves in this witty, beautiful story, which is by far the most assured and entertaining Doctor Strange tale I’ve read in many years. Vaughan’s wry take on the Stephen Strange/Wong relationship is perfection, and so is his use of Florence Nightingale fetishist Night Nurse, a salty structural stand-in for Clea who uses bobby pins instead of spells. Who says Marvel doesn’t know a thing or two about style?

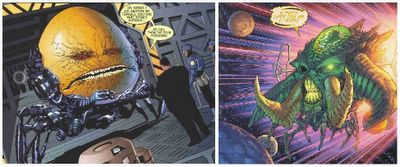

Annihilation #4 – The exciting twists and turns of this space saga are further evidence that Marvel needs to liberate both its writers and its fans from the creative quagmire of Civil War a.s.a.p. Annihilation is a “traditional” space saga—by which I mean, it has an entertaining story, appealing characters, and beautiful art. This issue contains some satisfying revelations about Annihilus’s plans and gives more airtime to one of my favorite second-string Avengers: Moondragon. Oh, and it features one titanic ass-kicking. The best issue so far of a series that is shaping up to be outstanding. If only the Marvel webmasters could succeed in matching the covers with their correct issue descriptions in their on-line catalog (the actual cover to this issue is here). While they’re at it, perhaps they could make the Marvel website legible. Even after its reorganization, it is still, hands down, the most unnavigable company site on the web.

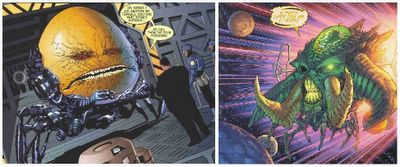

52 #25,#26, and #27 – There’s no shortage of things to praise about 52, but one thing I’m especially enjoying is its revival of DC’s more freakish characters, as well as its invention of new ones. Oh, Grant Morrison.

Is Chang Tzu “Egg Fu”? And more importantly, why do both he and Emerald Eyed Ekron have all those crazy robot legs?? (And who’s “driving” Ekron??? Or do my eyes deceive me?) Can we expect more disturbing monster-heads? 52 is so entertaining that someone is going to have to invent a special industry award just to honor it. Am also loving Ralph’s Orphic Odyssey. Not to mention the promised integration and rationalization of DC’s time-travel characters. Interesting too that the most recent issue appears to confirm my (and probably everyone’s) suspicion that the little girl on the cover of week 25 foreshadows of Renee Montoya’s future. R.I.P. Vic Sage; long live The Question.

Jonah Hex #13 – The already unmissable series gets gussied up a little further as Justin Gray & Jimmy Palmiotti are joined by international comics artist Jordi Bernet to tell the origin of Jonah Hex. The story is gripping and the interior art every bit as rich and expressive as the superb cover image suggests. What a treat, for as good as this series has been, the charm of this issue is that it actually looks like classic Western comic. Highly recommended.

Superman #657 – This is turning into one of the best Superman stories ever told. Seriously. Busiek is on fire writing an apocalyptic future in which Superman’s own body becomes the missile that send the earth into a state of nuclear winter.

The apocalyptic future has long been a cliché of the superhero genre, but it feels different this time. The “superteam” of Luthor, Lois, Jimmy, and Parasite on the cover is...so cool. And Pacheco’s art…gasp! The cover. The two-page spread of Metropolis falling into the sea. Everything here is just so beautifully rendered. I have nothing intelligent to say about this except: more please!

Teen Titans #40 – This was a good issue. But precisely because it was good, it also reveals the main limitations of the current series. When I finished reading it I thought: “Well, that was…moderately fun. It reminded me of some great stories from the past.” But, unfortunately, that’s about the most I could say about it. As my various Teen Titans posts over the past year and half have indicated, I’m tremendously ambivalent about this series, despite my nearly sycophantic admiration for Geoff Johns’s work on virtually every other title we writes, and despite (or perhaps because of) my fetish for the Titans era that Johns’s current series is attempting to emulate. I really like the One Year Later team; for the first time since the end of Wolfman’s brilliant Titans-Hunt saga, Johns has created a Titans team that could be spectacular. The group has energy, dynamism, and strikes a winning balance between novelty and tradition. And yet, despite a lot of action, globetrotting, new characters, and revelations, the actual story of this team still feels like it hasn’t started yet. I’m still asking myself, who are these characters? Who (especially) is Raven? And not in a gee-I-can’t-wait-to-find-out kind of way. More like an annoyed, wtf? kind of way. Similarly, the reveal at the end of this issue was enjoyable. But in a Johnsian universe, it was also inevitable (even though, I admit, I hadn’t predicted it). My complaint is that being caught by surprise this way can only be a mild thrill, and after awhile, begins to feel like a cheap trick if it isn’t supported by the kind of intricate character development and extended serio-comic “a day in the life…” downtime that was a hallmark of the classic New Teen Titans upon which so much of a reader’s enjoyment of the current series depends. What I don’t like about the current series, then, is its selective use of those Wolfman-Perez stories: it keeps much of their content, but throws out the form. What this new series has made me realize is that (nostalgia aside) my love of those earlier tales had as much to do with their formal density as with their treatment of plot and character. And of course, the two things are inseparable. Between Wolfman’s verbosity and Perez’s super-compressed, multi-panel pages, the classic New Teen Titans actually had room to deliver substantial doses of action and reflection every issue. The Johns/Daniel stories, however, are still too decompressed to do this adequately, so instead, they tend to build character development and reflection into their action sequences, sequences which are themselves simultaneously rushed (because there are too few panels per page) and overextended (because they take up so much of each issue). The result is a frenzied pace that never quite allows the team to gel. For an older fan like me, it all feels a little too much like the proverbial sound and fury… And yet, fulfillment is so close, you can almost taste it. Gah!

Annihilation #4 – The exciting twists and turns of this space saga are further evidence that Marvel needs to liberate both its writers and its fans from the creative quagmire of Civil War a.s.a.p. Annihilation is a “traditional” space saga—by which I mean, it has an entertaining story, appealing characters, and beautiful art. This issue contains some satisfying revelations about Annihilus’s plans and gives more airtime to one of my favorite second-string Avengers: Moondragon. Oh, and it features one titanic ass-kicking. The best issue so far of a series that is shaping up to be outstanding. If only the Marvel webmasters could succeed in matching the covers with their correct issue descriptions in their on-line catalog (the actual cover to this issue is here). While they’re at it, perhaps they could make the Marvel website legible. Even after its reorganization, it is still, hands down, the most unnavigable company site on the web.

52 #25,#26, and #27 – There’s no shortage of things to praise about 52, but one thing I’m especially enjoying is its revival of DC’s more freakish characters, as well as its invention of new ones. Oh, Grant Morrison.

Is Chang Tzu “Egg Fu”? And more importantly, why do both he and Emerald Eyed Ekron have all those crazy robot legs?? (And who’s “driving” Ekron??? Or do my eyes deceive me?) Can we expect more disturbing monster-heads? 52 is so entertaining that someone is going to have to invent a special industry award just to honor it. Am also loving Ralph’s Orphic Odyssey. Not to mention the promised integration and rationalization of DC’s time-travel characters. Interesting too that the most recent issue appears to confirm my (and probably everyone’s) suspicion that the little girl on the cover of week 25 foreshadows of Renee Montoya’s future. R.I.P. Vic Sage; long live The Question.

Jonah Hex #13 – The already unmissable series gets gussied up a little further as Justin Gray & Jimmy Palmiotti are joined by international comics artist Jordi Bernet to tell the origin of Jonah Hex. The story is gripping and the interior art every bit as rich and expressive as the superb cover image suggests. What a treat, for as good as this series has been, the charm of this issue is that it actually looks like classic Western comic. Highly recommended.

Superman #657 – This is turning into one of the best Superman stories ever told. Seriously. Busiek is on fire writing an apocalyptic future in which Superman’s own body becomes the missile that send the earth into a state of nuclear winter.

The apocalyptic future has long been a cliché of the superhero genre, but it feels different this time. The “superteam” of Luthor, Lois, Jimmy, and Parasite on the cover is...so cool. And Pacheco’s art…gasp! The cover. The two-page spread of Metropolis falling into the sea. Everything here is just so beautifully rendered. I have nothing intelligent to say about this except: more please!

Teen Titans #40 – This was a good issue. But precisely because it was good, it also reveals the main limitations of the current series. When I finished reading it I thought: “Well, that was…moderately fun. It reminded me of some great stories from the past.” But, unfortunately, that’s about the most I could say about it. As my various Teen Titans posts over the past year and half have indicated, I’m tremendously ambivalent about this series, despite my nearly sycophantic admiration for Geoff Johns’s work on virtually every other title we writes, and despite (or perhaps because of) my fetish for the Titans era that Johns’s current series is attempting to emulate. I really like the One Year Later team; for the first time since the end of Wolfman’s brilliant Titans-Hunt saga, Johns has created a Titans team that could be spectacular. The group has energy, dynamism, and strikes a winning balance between novelty and tradition. And yet, despite a lot of action, globetrotting, new characters, and revelations, the actual story of this team still feels like it hasn’t started yet. I’m still asking myself, who are these characters? Who (especially) is Raven? And not in a gee-I-can’t-wait-to-find-out kind of way. More like an annoyed, wtf? kind of way. Similarly, the reveal at the end of this issue was enjoyable. But in a Johnsian universe, it was also inevitable (even though, I admit, I hadn’t predicted it). My complaint is that being caught by surprise this way can only be a mild thrill, and after awhile, begins to feel like a cheap trick if it isn’t supported by the kind of intricate character development and extended serio-comic “a day in the life…” downtime that was a hallmark of the classic New Teen Titans upon which so much of a reader’s enjoyment of the current series depends. What I don’t like about the current series, then, is its selective use of those Wolfman-Perez stories: it keeps much of their content, but throws out the form. What this new series has made me realize is that (nostalgia aside) my love of those earlier tales had as much to do with their formal density as with their treatment of plot and character. And of course, the two things are inseparable. Between Wolfman’s verbosity and Perez’s super-compressed, multi-panel pages, the classic New Teen Titans actually had room to deliver substantial doses of action and reflection every issue. The Johns/Daniel stories, however, are still too decompressed to do this adequately, so instead, they tend to build character development and reflection into their action sequences, sequences which are themselves simultaneously rushed (because there are too few panels per page) and overextended (because they take up so much of each issue). The result is a frenzied pace that never quite allows the team to gel. For an older fan like me, it all feels a little too much like the proverbial sound and fury… And yet, fulfillment is so close, you can almost taste it. Gah!

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Kryptonian Fathers, Kryptonian Sons

Action Comics #844 – I wasn’t sure about this at first, but now that I’ve adjusted my brain to recognize this as a Richard Donner Superman film in the form of a comic (not a regular DCU Superman book), I’m enchanted. The orphan’s fantasy of recovering the absent father that pervades the Donner films is the driving force here too as Superman intervenes in what appears to be his own story being played out a second time. This is a compelling premise because while Superman’s intervention in this issue brings his own position in the orphan/foster-father narrative full circle, it does so in a way that may allow him to heal the initial gap between himself and the ghost-father/Mighty Oz, Jor-El. By becoming the space-boy’s guardian, Superman consciously steps into the role of archetypally good foster-father, Pa Kent; yet, because he and the boy are (apparently) both Kryptonian, Superman potentially transcends the position of “alien” foster-father to symbolically recover the original absent father, Jor-El—that is, he recovers his own father by “becoming” a “real” Kryptonian father in relation to a “real” Kryptonian boy/self.

No doubt, complications will ensue to muck with the promise of such mythic fulfillments. But it’s a tantalizing premise all the same, and its pathos is enhanced by the “filmic” visuals supplied by Adam Kubert in this issue. By “filmic” I don’t mean “grand” or “panoramic,” but quite the opposite: strangely subdued, realistic, plain. The banal details of the lab make it feel ordinary. Superman hovers cross-legged talking with the boy as he eats a sandwich on plastic toy furniture. The cubicles at the Daily Planet where Lois is working late have an exceptional degree of cinematic vraisemblance. There are no “supervillains,” yet. Barely any powers. That’s why the action sequences feel heavy—rather like “special effects.” (Could the producers not afford a conceptual artist to design a convincing spaceship? Is that why the child is “delivered” to earth in a giant wheel of brie?)

But this isn’t a criticism. What I am describing is the “austerity” that Hollywood cinema brings to the superhero movie because budget constraints require a stingy and very deliberate parceling out of visual departures from everyday realism. Superpowers are expensive, which is why the movie-Superman and his spandex-clad fellows spend so much time acting as brooding metaphors in superhero cinema rather than tossing bad guys around. When this kind of situational austerity is transferred to comic books—usually in adaptations of superhero films—the effect is almost invariably ugly, boring, and depressing. (I don’t think I’ve ever read a comic book movie adaptation that I’ve liked. And of course, that’s partly because such things aren’t written for me anyway; the adaptation is a “mediating” genre written for film goers who don’t read comics, though it’s hard to imagine that they’d be convinced to try more by such labored introductions.) Here, however, the Johns/ Donner script and Kubert’s translation of the restraint and austerity that comes from Donner’s (and Johns’s) film background produces a deeply gratifying effect, perhaps because the story is not an adaptation and because the paring down of the “color” of the regular DC Universe in the pages of Action Comics gives the plot a melancholy and nostalgic feeling that fits.

And there’s something else too. In a story like this, whose main concerns are thematic (and not intrinsically tied to the superhero genre, even if they find in its tropes a particularly congenial form of expression), the shift from a comic book aesthetic of spectacle to a filmic aesthetic of superhero “realism” confers a significant advantage. Namely, the reduction of ordinary spectacle means that the moments in which “special effects” are employed resonate with unusual power. The image of the boy holding the entertainment unit over his head is extraordinary, but we’d barely notice it in an ordinary superhero book. The same is true for the remarkably evocative illustrations of Superman sitting with the boy as he eats his sandwich or talking over his case with the scientists while the boy lays asleep in the racecar-shaped bed. These images take us to the heart of an emotion that runs deep and is, I suspect, fundamental to Superman’s continuing appeal, particularly for men who can no longer lay claim to the territory of boyhood, despite their most ingenious and self-flattering efforts. That these images are set within a story about relationships between sons and fathers is not coincidental. The feeling they evoke is not one that I expected myself to be moved by, because it is almost too corny to name. But as I get older, it’s one that, increasingly, gives me pause. Especially when it is presented as delicately and earnestly as it is here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)