[Spoilers]

There is one utterly magical scene in X-Men 3: The Last Stand.

Although I haven’t seen the first two films recently, I’d even go out on a limb and say that it’s the single best scene of all three X-Men movies combined. It’s almost enough to convince me that Brett Ratner is as good a director as he says he is.

I’m referring, of course, to Jean, Xavier, and Magneto in the flying house. This is Wizard of Oz territory…through a glass darkly. And it is the best death scene of a major good-guy character in a sci-fi film since Obi-Wan Kenobi disappeared into his cloak with a touch from Vader’s light saber in 1977. Not even the sneaky reveal that follows the film’s final credits can spoil the tragic splendor that this scene achieves.

Why does it work? For one thing, Jean’s transformation into Phoenix is totally credible and visually spectacular—it makes one pine for the lost opportunity of an all-Phoenix script (more on the later). The slow levitation of Xavier from his chair; the terrifying moment when Jean performs the simple act of standing up; the use of silence; the distortion of Patrick Stewart’s face with a wind machine to suggest Jean’s incalculable power; the subtle, CGI Phoenix-effect that seems to blast away bits of Professor X’s skin like flakes of stone, as if he is looking into the eyes of a fiery Medusa—all of these details are just perfect. Having Magneto sprawled helpless on the floor, beneath the kitchen sink, watching these titans clash, watching the destruction of his friend and rival is a wonderful detail, rich with ambiguous affect. And then there’s Wolverine’s slow progress across the ceiling towards the sealed room, anchored by his claws, and the final awful glance he exchanges with Xavier…

Sometimes we say, a little more enthusiastically than we mean to, that a single scene is worth the price of admission. In this case, it’s literally true. It’s a shame, though, that the best scene of the film, if not the entire X-franchise, occurs about 30 minutes into the movie. What follows is a maddening hour or so of storytelling so sloppy that not even the masterful Ian McKellan (who proves once again that he can elevate anything he touches—even without Magneto’s mutant powers) and a posse of nifty new mutants can salvage it.

What went wrong?

A better question would be: what didn’t? For starters, the plot achieves virtually no dramatic tension and delivers no real emotional pay-off. Even worse, and with the notable exception of the flying house, it squanders its cast and effects, undermining potentially gripping scenes at every turn. This is most obvious when one compares Xavier’s death scene to the other two major death scenes in the film.

Or should I say death scene—singular. Poor Scott.

Scott’s unceremonial ousting was also perhaps a side-effect of the expanded role for Halle Berry’s Storm. Berry, miscast from the beginning, and present only because the studio was worried that they needed a big name to draw the crowds to the first, untested X-film, is far and away the worst of the core cast members: she’s a talented actor no doubt, but she just doesn’t get superheroes. James Marsden may not have the star-power of a Halle Berry, but at this point, even if you like Berry’s stiff, bewigged den-mother performance (and frankly, I find that hard to believe), does it really matter? Is anyone really going to see X3 because they’re dying to see Halle Berry throw a lightening bolt in that absurd Jim Lee-inspired disco costume? In the comics, I’ve always preferred (punk) Storm’s leadership to Cyclops’s, and the angst-ridden showdown between Ororo and Scott for leadership of the X-Men in the Danger Room battle from Uncanny X-Men #201 is a classic. The shrug-inducing supplanting of Cyclops by Storm for leadership of the team in X3 epitomizes everything that is wrong with the film dramatically. Scott is simply removed by a fire-tressed deus ex machina and Xavier provides a lame justification for replacing Scott with Storm: he’s “changed” since Jean’s death. Huh? You mean he’s in mourning for his wife, therefore the Professor dumps him? Look into Patrick Stewart’s eyes when he tells Berry’s bewildered Storm about her promotion—not even he’s good enough of an actor to sell that explanation.

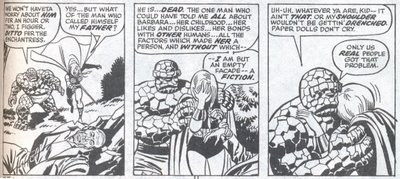

The clumsy dispatching of Cyclops is matched by (and to some extent is responsible for) the banality of the movie’s climactic death scene too. Logan’s killing of Jean should be gut-wrenching, but it feels hollow. There’s no emotional pay-off because, despite the torch he’s been carrying for her since the beginning and despite the white-hot chemistry between Jansen and Jackman, the movie doesn’t adequately establish this pair as a romantic couple on screen to make us feel the horror of what Wolverine must do. I’m sorry, but a make-out session with Phoenix and one growly “I love you” aren’t enough. Ironically, this scene would have played much better if poor dead Scott had been in Wolvie’s shoes, or even if he was simply a witness to Jean’s death (as Magneto was to Charles’s) since he and Jean at least have a fully developed relationship. Had Scott not been killed, and had he and Jean enjoyed a genuine reunion before the Phoenix completely possessed her, Scott’s anguish at the beginning of the film might have provided the basis for a truly affecting conclusion as we are forced to watch him regain his partner only to lose her again. As it is, we’re stuck with Wolverine’s unintentionally bathetic sob (the audience laughed) as the movie gives us a neat but empty simulation of a similar but much cooler scene from Grant Morrison’s New X-Men.

Yes, I know. I am a bitter, bitter fanboy, whining that the comic was better. And YES, I know that the films must obey their own dramatic logic and not feel bound to slavishly recreate the source material from twenty-some years of comic book continuity. But the film fails even on the more limited ground of filmic coherence. Its replacement of Scott with Logan is so shabbily and hastily done that the final scene between Wolverine and Phoenix is all special effects and no heart.

And this is too bad, because they almost had something great. We all understand the codes of a resolution like this: by “killing” Jean, Wolverine is elevated to the status of tragic hero. Moreover, the film’s violent climax is also a sublimated consummation of the Logan/Jean relationship. We understand that he is really killing “Phoenix,” not Jean, and in this way, Wolverine gets to have his cake and eat it too. Symbolically he “gets the girl,” but (ironically, given the circumstances) also keeps his hands clean because, technically, he doesn’t really get her: the consummation of their love remains only symbolic and sublimated—in other words, he doesn’t sleep with Scott’s girl, not even after she’s a widow. What makes this all so frustrating is that in many ways it is a perfect resolution: it maintains Wolverine’s role as noble tortured outsider who can never really have the girl, and must thus release his pent up energy in lone flourishes of Berserker rage. But because Scott’s dead, the one character whose anguish and sense of betrayal could invest this climax with some real human feeling is missing, so Wolverine is forced to inhabit the role of tortured leading man. For me, it didn’t work, because Wolverine’s supplanting of Scott’s role happens much too fast. This transformation would have worked better, I think, if it had been given more time to develop and if Scott, Jean, and Wolverine had been the focus of the film—in other words, if X3 had basically been a filmic version of “The Dark Phoenix Saga” and completely dropped the poorly handled “mutant cure” plot, deferring it for a fourth installment of the film. What the overstuffed, underdeveloped plot of X3 shows us, very clearly, is that the X-Men should have been conceptualized as a 4-part series (with part three set in the Hellfire Club environs), not a trilogy.

In addition to creating a pacing problem in the Scott/Jean/Logan triangle, the screenwriters’ decision to intertwine the Phoenix story with the “mutant cure” plotline has several other, more serious consequences. On a very basic level, these two plots just don’t mesh well, despite the literalist retooling of Phoenix into an id-like split personality for Jean. Even if she is pissed off with the human race, why on earth does a “level five mutant” need to spin her wheels with Magneto’s Ewok brotherhood? (Is there some rule I don’t know about that requires disappointing third-installments of science fiction trilogies to be set in rainforests? I kept expecting Wicket and friends to drop from the treetops onto the unsuspecting backs of the government’s keystone shock troops. Self-duplicating Jamie Maddrox’s tribe-producing decoy was the next best thing, I guess. Perhaps a filmmaker’s clever jab at the primitivist logic of the Ewoks whereby all members of foreign tribes seem to “look the same” to the racial outsider? We should be so lucky. And boy, do I digress…) The bottom line is that in order for Jean’s reality-altering Phoenix to “work” within the context of Magneto’s war against the mutant cure, Jean has to be put on ice for most of the film. Why is she chilling with Magneto in the woods for 40 minutes? Because Brett Ratner needs to have Wolverine kill her later in a dramatic set-piece ending. Oh, okay. But really, who wants a Phoenix with clipped wings? The more I think about it, the more I love the Warren Worthington/Angels in America allegory, which picks up where Bobby’s coming-out scene from X2 leaves off, but those few soaring moments do not make up for the script’s unforgivable grounding of the film’s other great winged wonder.

The other obvious narrative and aesthetic weakness of the “mutant cure” plot is the introduction of Fraiser Crane’s wretched Beast. Oh my stars and garters. I like the Beast in the comic books well enough, I guess, but suffice it to say that Jar Jar Binks finally has some company in the film-ruining character Hall of Shame.* What CGIed, flatulent Jar Jar was to live-action/cartoon hybrids, Hank McCoy’s blue “Furball” is to Chewbacca-style hair, body paint, and prosthetics: in both cases, the originals were far better. Did X3’s costuming department run out of money? In a single stroke, this pretentious, cheap-looking team mascot demotes the franchise from A-level film, to B- or C-level direct-to-video hackery. Everyone knew that casting pudgy windbag Kelsey Grammer as a gleefully bouncy mutant superhero was a horrible mistake (only Robin Williams could have been worse). But frankly, I’m not sure that any actor could have made this visually absurd character work on screen. As I’ve mentioned in painstaking detail before, the absolute greatest danger besetting any superhero film is the high likelihood of looking ridiculous. There’s no other way to say this: there should have been no Beast. And while I’m on the subject, having the Beast, the BEAST, deliver what was in effect a fatal blow to Magneto is quite possibly the most incomprehensible dramatic choice the movie could have made. Literally anyone would have been a better agent of Magneto’s downfall—though having Mystique/Raven deliver it directly would probably have been the most satisfying choice.

All this dramatic and narrative bungling is bad enough, but my undying ire for Ratner’s mutant fiasco is reserved for the film’s ideological betrayal of every principle that made the first two X-Men movies meaningful, pertinent, and occasionally inspiring.

The film repeatedly gestures—most gracefully in the gay-Angel subplot—at the mutant-as-metaphor-for-difference principle that has underpinned the X-Men concept from the very beginning and which is foregrounded throughout the first two films. But these gestures are belied by the film’s flagrant ideological copout, which turns the X-Men into apologists for the very forces of homogeneity and repression (embodied, as ever, by the government) against which they are usually arrayed.

Simply put: Magento is more right than he is wrong. The state does want to exterminate mutants, it will draw first blood, and this is a war. Now, I know what you’re thinking: yeah…but some of those mutants are dangerous! And what about poor Rogue? She can’t even cuddle with her boyfriend Iceman who’s already ditched her to skate chastely around the pond with Kitty! Doesn’t she deserve the right to choose whether she takes the cure or not? Not all mutant powers are good!

But don’t be fooled: this is the film’s most ingenious and underhanded trick. It’s called sleight-of-hand.

Remember that every metaphor is a comparison that has a tenor and a vehicle. In the cheesy phrase, “My beloved is a jewel,” “jewel” is the vehicle (the metaphorical symbol) for “beautiful” or “precious” (the tenor or implied concepts to which the vehicle refers). Similarly, “a mutant” in the X-Men films is the vehicle for “difference”: racial, sexual, gender, etc. It’s common knowledge that this is the basis of the films’ and the comics’ political allegory.

For those of us who approach the films with some sense of this political allegory (and how can we not? they all broadcast it explicitly), it’s difficult to argue with Magneto, whose call to arms is basically a rallying cry on behalf of difference against the tyranny of sameness (racism, homophobia, anti-Semitism and all its other manifestations). This has been Charles Xavier’s argument throughout the films as well. In other words, Magneto’s call to arms makes visceral sense to most of us on the level of the metaphor’s “tenor”—i.e. its real-world referent.

So how on earth does the film justify the bizarre turnabout by which the X-Men end up functioning as government patsies in the so-called “last stand”? It does so by cunningly (and unconscionably) switching from the level of the mutant-metaphor’s tenor (real-world difference) to its vehicle (fantasy-world mutation). In other words, because Magneto’s argument and actions are morally compelling at the level of the metaphor’s tenor (in the real world, we should all fight against racism and homophobia) the film can only provide a sort of pseudo-justification for the X-Men’s actions by retreating to the level of the metaphor’s superficial vehicle, that is, by acting as though mutant powers are real and by behaving as though what’s really at stake is the right of mutants to choose whether or not they want to keep their powers. Of course, this type of “choice” doesn’t make any sense on the level of the real-world tenor (a gay or black or Hispanic person does not have the option of a “mutant cure” and the whole point of the mutant metaphor is to say that framing the question this way in the first place is an obscene mystification). X3’s sneaky switch from the allegorical level of the tenor to the superficial level of the vehicle to justify its betrayal of the franchise’s politics is an object-lesson in how popular narratives exploit the double-level of allegorical narrative structures to produce deeply reactionary forms of art—and this is only one of the ways in which the film is a giant ideological copout that undermines the trilogy’s pop-radicalism in a way very similar to that dreadful final Matrix picture.

The somewhat more obvious markers of the ideological copout I’m talking about are (1) Magneto’s “evil mastermind voice” during the rally in the woods (a voice which McKellan presents with incredible restraint, as if he was secretly resisting the absurdity of the script and, likely, Ratner’s direction too) and (2) the embodiment of the mutant cure in innocent bubble-boy, Leech, who seems to be imprisoned in (and groomed by the stylists of) one of the austere cubicles from George Lucas’s THX-1138. How do you make the X-Men fight to defend an indefensible cause? Embody said cause in a sweet, innocent little lamb! Only an evil mutant terrorist like Magneto would harm a hair on the head of such a tender darling—oh wait, he has no hairs on his head. See what I mean?

And then there’s Xavier’s suppression of Jean Grey’s Phoenix personality. Now, suddenly, the reason for the incommensurable twining of the Phoenix story and the “mutant cure” story leaps into view. Clearly we’re supposed to understand Jean’s deadly id as another justification—indeed the main justification—for the X-Men’s qualified defense of “the right to choose” a “cure” for difference. After all, Wolverine himself kills her, becoming a sort of double for Leech, a more feral embodiment of the regrettable, but “necessary” cure. And Logan cries, of course, to show us that “cures” like this are a sad, regrettable thing, but necessary all the same—for without Logan’s difficult choice, Phoenix would have us all for breakfast, wouldn’t she? (Allegorically, at least, I wish she would. Now THAT would be a movie.) The point is that, like Rogue’s tragic, alienating power, Jean’s Phoenix personality provides the film with what can only be called “moral pseudo-complexity,” implying that in some cases it’s necessary to suppress difference. You know, when it’s dangerous. (To whom exactly? When? And who are the terrorists again? Ah…yes…)

As with Rogue, at the level of the vehicle (which is to say, literally), Xavier is morally justified in suppressing the Phoenix-power. The destructive Phoenix personality can hardly wander around unfettered. Indeed, Xavier’s mental powers act as a sort of “super”-ego here, for by repressing Jean Grey’s “super” id, he is doing no more than maintaining the general balance that all people maintain between desire and repression in order to live in society without raping, killing, and eating everyone in their immediate vicinity. At the allegorical level of the tenor, however, Xavier’s act is simply a callow anticipation of Leech’s and Wolverine’s various enactments of the suppression of difference. When read in this light, against the grain of the film’s coding, but with the grain of its implicitly conservative ideology, that sad parting smile that Professor X shoots Wolverine in the vortex of Jean’s disintegrating family home is a kind of sinister passing of the torch—an implied sanction for what Wolverine “must” eventually do.

Did it have to be this way? Absolutely not. The Professor’s suppression of Jean’s Phoenix power acquires its sinister meaning only from the context of the “mutant cure” storyline in the film. It should go without saying that there is nothing intrinsically unworkable about writing an intelligent Phoenix story that is consistent with, or even strongly in tension with, the foundational principle of respecting, even loving, difference that informs the X-Men concept. But by pairing the Phoenix story with the “cure” story, the film’s producers, writers, and director have, well…fucked it all up and betrayed the franchise’s principles. All without really trying.

Because, of course, they weren’t trying. X3’s ideas, like its plot, are a badly jumbled mess. Not surprising, since much of the film was reportedly shot without a script. The movie’s abrasively conservative ideology is not evidence of a right-wing conspiracy (that would be giving Ratner and his writers too much credit); rather it is the result of letting a banal, morally vacuous story concept (we need the “good” mutants to fight the “evil” mutants!) overtake the film’s more interesting allegorical possibilities. And let’s not forget that all the major stars of this sales record-breaking franchise were only ever committed for three movies. How do you keep the X-Men juggernaut going without Patrick Stewart, Ian McKellan, Hugh Jackman, Famke Jansen, James Marsden, Anna Paquin, and Halle Berry? Transplant Xavier’s consciousness into a new actor’s body; de-power Magneto; kill Cyclops and Jean Grey. As for the rest, it’s never been hard to explain a few absences around the X-mansion: Logan is off doing his lone wolf thing in his own movie; a now human Marie (Rogue) has gone off to sow some wild oats; and Storm—well, who cares about her anyway? The deaths of the principals in X3 had nothing to do with telling a good story, and everything to do with “tying up the loose ends” so that Marvel could reboot the franchise as the New Mutants with cheaper, younger actors at some future time.

The fact that the film’s conservatism is unintended is no excuse, and has no bearing on the final product. Were my expectations for this film too high? Obviously. But the carelessness with which X3 was handled makes me angry because movie properties like X-Men—properties that have a global reach, which speak directly to kids, and which advertise their moral/philosophical pretensions—have a responsibility to follow through on the ethical vision they promise, even if those ethics are sometimes cartoonish and oversimplified. In short, these are relevant and potentially influential cultural narratives. They deserve better and so do their audiences. Didn’t someone once say, “with great power comes great responsibility”? Oh, wait, that’s right—Brett Ratner isn’t a comic book fan. Never mind.

Movies—good and bad—often contain scenes that come to stand, retrospectively, for the film as a whole. The microcosm of X3 is not, alas, the wonderful floating Grey-family home, with its extraordinarily allusive potential. It’s not even the messy, noisy, anti-climactic final battle between Magneto and his “evil” mutants, though it nearly could be. Instead, it is that awful tableau of Kitty Pryde standing on Astroturf before the cheap-looking Styrofoam headstones of Xavier, Jean, and Scott. A ghost mourning for ghosts. Is this what the once-scrappy X-Men franchise has come to? A dour simulation of gravity? An awed respect for elders? A tragic myth of origins? Let’s hope the kids of X4: New Mutants will remind us what it’s like to soar.

NEW! >> For a very different analysis, check out Thomas’s awesome response-essay defending X3 here.

NEW! >> The debate continues over on David Golding’s Pah!, here and here.

NOTES >> *For an excellent defense of Jar Jar Binks and of the newest Star Wars trilogy generally, see David Golding’s extensive film notes. (Sorry to be bashing Jar Jar again David!)